Part 2: Our detailed assessment

2.1

In this Part, we set out our assessment of the Police’s progress toward fully implementing each of the Commission’s applicable recommendations. The assessment is organised sequentially by recommendation number.

2.2

For each recommendation, we reproduce the wording of the Commission’s recommendations, describe the work that the Police have carried out in response, then set out a summary of our assessment.

2.3

Overall, we have assessed that the Police have fully implemented seven of the Commission’s 47 recommendations.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R1

New Zealand Police should review and consolidate the numerous policies, instructions, and directives related to investigating complaints of misconduct against police officers, as well as those relating to the investigation of sexual assault allegations.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.4

An independent review of the Police’s policy capability reported in 2006 that:

Currently most groups within the Office of the Commissioner issue policy instructions and guidelines. Processes are somewhat ad hoc. There is no consistency of format and style. Sign-off arrangements differ. There is no consistent ongoing oversight of instructions and guidelines and as a result many are out of date. Instructions are not held in one place and are difficult to access by Police staff in the districts. There is confusion as to whether they are mandatory ‘must do’ instructions or simply guidelines.

2.5

The Police have made good progress in addressing these issues.

2.6

The Police have established a Corporate Instruments team of five people in the Policy Group, which is based in Police National Headquarters. The team works on operational policies. The team has been asked to:

- prepare a framework for integrating the Police’s corporate instruments;

- review and align the documents within this framework; and

- establish a process and library for preparing and distributing the corporate instruments.

2.7

The work of the team is wider than the policies, instructions, and directives relating to the investigation of complaints of misconduct against police officers and investigation of adult sexual assault complaints.

2.8

The team has been responsible for overseeing the review of:

- all national operation and administrative policy, orders, instructions, and guidelines (including memoranda of understanding) by the Police’s national business groups and service centres; and

- district orders and other local policy and instructions by district commanders.

2.9

The issuing of a Commissioner’s Circular (2008/04) in 2008 has supported this review work.

2.10

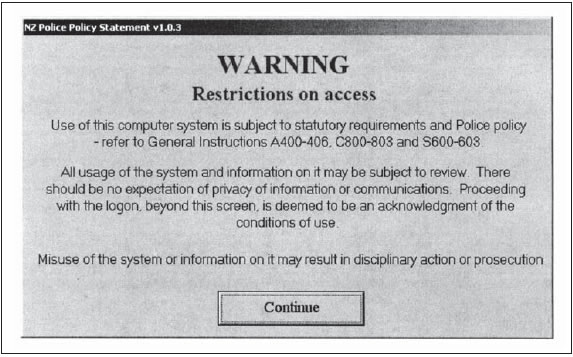

As part of the review work, the team has established a single electronic site where all corporate instruments are stored. This is known as the Police Instructions Intranet site. The site includes national as well as local orders prepared by districts and business groups. The Corporate Instruments team publishes local orders on the Police Instructions Intranet site. All local orders are reviewed by the Corporate Instruments team leader before publishing.

2.11

The ASA Investigation Guidelines and complaint investigation process are available on the site. There is also evidence of consolidation and updating of the predecessor documents to the ASA Investigation Guidelines.

2.12

The team has set up policies and procedures for preparing, maintaining, publishing, and cancelling general instructions3 and local orders. The policies and procedures put in place should reduce duplication, improve consistency, reduce conflict, and improve the currency of the corporate instruments. The procedures also require individual instruments to be reviewed at least once every two years.

2.13

Although the Police have reviewed and consolidated their corporate instruments, the review and consolidation is ongoing. For example, there were 1400 general instructions in 2006, and at the time of our audit fieldwork there were 535. By the end of the review, the Police want to have 10 general instructions that address the most critical policies. Because of the number of instruments involved, the Police have decided that what is most important is that people know where the documents are stored and can find them.

2.14

Information provided to us by the Police indicates that, between June and October 2009, 2302 corporate documents, including general instructions, had either been amended or published as new documents. This includes various documents relating to complaints, investigations, and interviews. It does not include the ASA Investigation Guidelines.

2.15

The extent of amended or new documents illustrates the large number of corporate instruments the Police have and the challenges an individual employee faces in being aware of the documents that are relevant to them. In our view, the Police have used a logical categorisation of documents on the Police Instructions Intranet site to help users find a document.

Summary

2.16

The Police have reviewed and consolidated some of their corporate instruments, including those about investigating complaints of misconduct and allegations of sexual assault by police staff. There is still work to do, and this review and consolidation is continuing.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R2

New Zealand Police should ensure that general instructions are automatically updated when a change is made to an existing policy.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.17

Individual business groups within the Police decide whether to prepare, renew, or update a general instruction. The template for issuing a general instruction requires a review date to be specified.

2.18

When the date is reached, the owner of the general instruction will receive an automatic reminder to review the document. The notification, but not the actual updating of a general instruction, is automatic.

2.19

Changes to an existing policy do not trigger the automatic reminder nor ensure that any related general instructions are updated accordingly.

Summary

2.20

The Police have set up an automatic reminder process for when a general instruction reaches its review date. This does not guarantee that the general instruction will actually be updated then. The Police have not set up a method or process for ensuring that general instructions are updated when they reach their review date, or for ensuring that policy changes will automatically update any related general instructions.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R3

New Zealand Police should develop a set of policy principles regarding what instructions need to be nationally consistent and where regional flexibility should be allowed.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.21

The Police have a devolved management structure. Within this structure, national and district managers have the discretion to decide whether to initiate a corporate instrument and the form of this instrument. General instructions are orders or instructions that require absolute compliance and accountability by all Police employees.

2.22

There is some guidance available to managers about when it is appropriate to use a general instruction. The instruction, once prepared, is also reviewed by members of the Corporate Instruments team (who primarily check format, completeness, and alignment with Police strategy) and the relevant national manager, and is approved by the Commissioner. The Police are still reviewing their general instructions, and until this task is finished the implementation of recommendation R3 will not be complete.

2.23

Local orders can be issued by particular senior staff within the Police. Local orders apply to all Police employees stationed or seconded in the applicable district or business group. They enable regional flexibility. The local orders are drafted by the district or business unit and are checked by the Corporate Instruments team before being published on the Police Instructions Intranet site. The local orders have to be consistent with and support strategic policy, direction, and outcomes, and not conflict with or duplicate national policy and outcomes.

Summary

2.24

The Police have established a framework that provides guidance on when instructions need to be issued at a national level, while providing for regional flexibility. If the guidance is followed, regionally developed instructions should be consistent with national policy and outcomes. This work is not yet complete.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R4

An enhanced policy capability should be developed within the Office of the Commissioner to provide policy analysis based on sound data, drawing upon the experience of front-line staff and upon research from New Zealand and beyond.

Our assessment: Completed by the Police.

2.25

The Police commissioned an independent review of their policy capacity and capability in late 2005. The reviewers reported in May 2006, and said that the Police "urgently needs to enhance its policy capacity".4

2.26

The reviewers were strongly of the view that the Police should increase the number of staff in the Policy Group to provide a strong central pool of policy expertise, and proposed a significant increase in the size of the Group. The Police generally agreed "with the thrust, findings and observations" in the report, and committed to providing additional resources.

2.27

At the time of the review, there were eight staff in the Policy Group. The Police aimed to increase this to 26 staff.

2.28

Decisions about the policy function were made before the Commission’s report was published in 2007, but occurred during the period the Commission was performing its work.

2.29

The Policy Group is now managed by the National Manager Policy and Legal Services. It consists of four teams, broadly covering:

- Justice and Transport policy;

- Crime and Social policy;

- Global policy issues; and

- Corporate Instruments (as described earlier in this Part).

2.30

We note that the Police have been producing policy-related advice on a number of issues that are of strategic significance to policing, including:

- a Methamphetamine Control Strategy (2009);

- advice on an Arms Amendment Bill (undated);

- DNA legislation (undated);

- Whanganui gang patch legislation (undated); and

- a submission on the Law Commission’s issues paper on the reform of New Zealand’s Liquor Laws (2009).

2.31

There was evidence in the policy work that we reviewed of the Police drawing on information and research from overseas.

2.32

To fill some places in the Policy Group arising from the secondment of staff to other areas, the Policy Group has had a series of six-month secondments from districts, usually seconding staff at sergeant or senior sergeant level. The Police’s view is that these secondees bring a variety of operational experiences to the Group, and take their understanding of the policies back to their district. At the time of our audit fieldwork, we were told that there had been five such secondees.

2.33

We consider that the Police now have an enhanced policy capability, and the secondment of frontline staff enables their operational experience to be drawn on as policies are prepared.

Summary

2.34

The Police have enhanced their policy capability and have frontline staff regularly working within the Policy Group.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R5

New Zealand Police should develop an explicit policy on notifying the Commissioner of Police when there is a serious complaint made against a police officer. This policy and its associated procedures should specify who is to notify the police commissioner and within what time frames.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.35

The Commissioner of Police issued a Circular for all staff (on 24 August 2009) requiring that the Commissioner be notified immediately when a police officer is the subject of a serious complaint. The Circular requires a Police employee receiving information about a serious complaint to take immediate steps to notify the appropriate district commander or national manager. It specifies the steps, and who is to notify the Commissioner, and requires this to be done immediately.

2.36

The Police told us that the approach in the Circular built on the practice they had been following since shortly after the Commission’s report was published.

2.37

The Police consider a serious complaint to be one that is of "such significant public interest it puts, or is likely to place, the Police’s reputation at risk". Examples of serious complaints included in the Commissioner’s Circular are:

- complaints against Police employees likely to generate significant media coverage

- complaints that would otherwise be considered not serious but involves Police employees at the level of position of inspector or above, or equivalent level senior managers who are not constables

- complaints that involve members of the Police Executive

- complaints against Police employees regarding incidents of a sexual nature.

2.38

We have viewed a list of 54 cases considered by the Police to be serious complaints against police officers since July 2007. In all but two cases, the date on which the Commissioner (or Acting Commissioner) was notified is recorded.

2.39

The Police need to ascertain that the Circular prepared to meet this recommendation is being fully complied with before the recommendation can be considered fully completed.

Summary

2.40

Staff within the Police have been instructed to inform the Commissioner of Police about all serious complaints against a police officer. The Circular sets out the requirements and general time frame for notifying the Commissioner of Police. The Police need to monitor compliance with the Circular to ensure that the intent of the Commission’s recommendation is being fully met.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R6

New Zealand Police should ensure that members of the public are able to access with relative ease information on the complaints process and on their rights if they do make a complaint against a member of the police.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.41

An effective complaints process helps to minimise the risks that inappropriate behaviour by any member of the Police pose to public confidence in the Police. Easy access to the mechanisms for making a complaint about a police officer is an essential part of an effective complaints process.

2.42

Information on how to make a complaint against a member of the Police, noting most of the methods, is provided in the Frequently Asked Questions section of the Police website (www.police.govt.nz). The methods include:

- visiting a police station;

- mailing or faxing a letter to any police station;

- writing to the Office of the Police Commissioner;

- contacting the Independent Police Conduct Authority by letter, telephone, or email, or by using the Independent Police Conduct Authority’s online complaints form;

- contacting a solicitor; or

- contacting the registrar of a District Court.

2.43

Other methods mentioned in Police documents and our interviews with members of the Police included making a complaint to an Ombudsman, approaching a local member of Parliament, and calling the Crimestoppers telephone line.

2.44

We performed a small (18 respondents) random telephone survey, with the Police’s permission. We telephoned police stations anonymously and asked for information about how to make a complaint against a police officer. The information we were given was mixed, and two respondents were not sure what we should do.

2.45

Although our survey involved only a small sample, the findings of our survey were consistent with our interview findings. In our view, the Police need to ensure that staff provide the public with consistent information about how to make a complaint and how complaints are handled.

2.46

The Police’s record of progress against their project milestones for the Commission’s recommendation R6 is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The New Zealand Police’s assessment of progress against project milestones for responding to recommendation R6 of the Commission of Inquiry into Police Conduct

| Description | Planned start | Planned finish | Actual start | Actual finish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Making information on the complaints process and complainants’ rights available on the Internet | 1 September 2008 | 29 May 2009 | 1 September 2008 | - |

| Scoping paper detailing scope, milestones, budget and time frames for recommendation R6 | 2 February 2009 | 27 February 2009 | 2 February 2009 | 27 February 2009 |

| Developing a complaint process and complainants’ rights document | 2 April 2009 | 13 November 2009 | - | - |

| Including complainants’ rights in the Service Charter | 1 July 2009 | 29 March 2010 | - | - |

| Developing a communications plan | 16 February 2010 | 29 March 2010 | - | - |

| Completing information pamphlets | 27 April 2010 | 10 May 2010 | - | - |

2.47

In our view, the Police need to complete the work that remains unfinished. Implementing a communications plan, for example, could help to ensure that Police staff adequately understand the complaints process.

2.48

The Police told us that they are preparing a pamphlet for the public and the Police about the complaints process.

Summary

2.49

The Police have more work to do to provide easy public access to information on the complaints process and to know that their staff are following the correct process. There is information about the complaints process on the Police website. Asking a police officer is less likely to provide reliable information about that process. The Police have not yet made information on the rights of complainants available, and have more work to do to improve staff and the public’s

understanding of the complaints process.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police implement plans for improving the information available to members of the public, including their rights and the process to follow when reporting inappropriate behaviour by police officers. |

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R7

New Zealand Police should undertake periodic surveys to determine public awareness of the processes for making a complaint against a member of the police or a police associate.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.50

The Police need to check that the public know about the complaints process. The Commission’s report suggested that a periodic survey might be an effective tool "to ensure that there is awareness amongst the general public that there are processes for making a complaint and that [members of the public] have defined rights when doing so".

2.51

The Police consider that a question in their annual citizens’ satisfaction survey addresses the Commission’s recommendation. The survey includes a question about whether respondents had "any problems or experienced any negative incidents or interactions" when receiving services from the Police. Respondents who answer "yes" to this question are then asked how strongly they agree or disagree that "It was clear what to do if I had a problem".

2.52

In the 2009 survey, 4% of respondents indicated having a problem or experiencing a negative incident or interaction with the Police. This is a relatively small proportion. Of these people, 40% indicated that they "agreed" that it was clear what to do about this and 40% indicated that they "disagreed" that it was clear what to do about this.

2.53

Surveying public satisfaction with services and seeking information from people who have had a negative experience with the Police is good practice. However, this information does not specifically assess public awareness of the existing complaints process. Respondents who agreed might not be aware of the actual process for making a complaint. Similarly, respondents who had positive experiences with the Police were not asked about their awareness of the complaints process.

2.54

To address the Commission’s recommendation, the Police will have to either include a question in their annual citizens’ satisfaction survey asking specifically about public awareness of the complaints process – and not just from the survey respondents who had a negative experience of the Police – or obtain this information through some other means.

2.55

The Police told us that their survey questionnaire will be reviewed in June 2010. They will then determine how best to address recommendation R7.

Summary

2.56

The Police carry out periodic surveys of public satisfaction with their services. However, the surveys do not provide the Police with assurance that members of the public are aware of the processes for making a complaint. To get that assurance, the Police need to get more specific information from a wider audience.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R8

New Zealand Police should develop its database recording the numbers of complaints against police officers to allow identification of the exact number of complaints and the exact number of complainants for any one officer.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.57

The Police have purchased and installed a software application, to be implemented nationally, to record complaints information which can be used to provide an early warning of inappropriate behaviour. The Police told us that they have been using the system since about May 2009. The system is called IAPro and is used by more than 250 agencies worldwide.5

2.58

The Police are also using a piece of software known as BlueTeam that allows district professional standards managers to input and extract information (with the appropriate confidentiality arrangements) from IAPro. This full functionality was not in place at the time of our audit fieldwork but aspects of it were being piloted in the Wellington District and in three Auckland districts.

2.59

We observed IAPro in action. It can report about an individual employee and can produce early warning alerts based on criteria such as the type of incident or type of force used, or the type of allegations made. The Police were not using this latter function at the time of our audit fieldwork and were still deciding "the science behind what will trigger an alert" about an employee.

2.60

The Police told us that information recorded in the system includes complaints, matters reported to the Police under the Memorandum of Understanding between the Police and the Independent Police Conduct Authority, employment investigations, and selected information previously recorded in the Police’s PeopleSoft human resources system.

2.61

The Police told us that, before IAPro, such information was stored in multiple databases and hardcopy files. The Police would have had to manually search the databases and files to answer any queries about a particular employee.

2.62

At the time of our audit fieldwork, the Police were reviewing the codes used in the system to classify types of complaints and allegations. There are 60 different categories covering aspects of external service delivery and internal performance matters.

2.63

We were told that IAPro can record the source of a complaint (including anonymous sources) as well as the type of complaint. Information such as Police station and workgroup names can also be recorded, which would enable the Police to identify and analyse patterns or trends.

2.64

At the time of our audit fieldwork, the only staff who could access the information in IAPro were in the Professional Standards and Employment Relations teams at Police National Headquarters. District professional standards managers could submit complaint information through BlueTeam. In the future, BlueTeam will be upgraded to allow district professional standards managers to view and update information on current investigations into employees in their districts. Until then, district staff contact the Professional Standards team for the information. The national manager of the Professional Standards Team has to approve the distribution of the information.

2.65

The risk with any warning system is that its effectiveness depends on one of two options. The first is that compliance monitoring identifies issues. The second is that individuals – police officers or members of the public – see the behaviour as inappropriate and are prepared to report it, and that full and accurate details are promptly recorded within the system.

2.66

The Police told us that they intended to make it easy for staff to raise issues by having telephone numbers for staff to call as part of their Employee Assistance Programme and the Crimestoppers initiatives. We commend the Police for intending to create multiple channels for staff to raise issues.

2.67

It is important that the full early warning functionality of the Police’s electronic complaints recording system be used as soon as practicable. In our view, and based on what we saw and were told during our audit fieldwork, the risk remains that inappropriate behaviour may not be seen as inappropriate or be reported.

Summary

2.68

The Police have put in place a specialised software application that has the capacity to record complaints against individual police officers, the number of those complaints, and the number of complainants. The implementation of this application is still in its early stages.

| Recommendation 6 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police start to fully use the early warning functionality of the electronic complaints recording system (IAPro) as soon as practicable, at both national and district levels, so that any inappropriate behaviour and resistance to change is regularly and systematically identified and followed up. |

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R9

New Zealand Police should review the implementation of the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Policy to ensure that the training and resources necessary for its effective implementation are available and seek dedicated funding from the Government and Parliament if necessary.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.69

The Police issued updated ASA Investigation Guidelines on 1 July 2009. The ASA Investigation Guidelines updated a 1998 version.

2.70

Although we have considered the ASA Investigation Guidelines to be the Police’s policy for investigating adult sexual assault complaints, we note that policy documents are generally different from guidelines. Policy documents usually outline higher-level principles (for example, investigations will be carried out fairly, promptly, and impartially), while guidelines outline the process for giving operational effect to these principles.

2.71

We encourage the Police to review the ASA Investigation Guidelines to ensure that they contain enough information of a policy nature.

2.72

The following aspects of the ASA Investigation Guidelines are important for effective implementation, and therefore what we would expect the Police to monitor.

2.73

The ASA Investigation Guidelines require that a specialist crisis response person is made available to the complainant early in the investigation, and that complainants be kept well informed throughout the investigation and judicial process.

2.74

The ASA Investigation Guidelines require the investigation to be assigned to an adult sexual assault investigator. If an adult sexual assault investigator is not available to deal with a complaint, and it is necessary to proceed urgently, then the reasons for this must be appropriately recorded on file. In these instances, the most suitable police officer should be assigned to the investigation.

2.75

The Police told us that, in some instances, parts of an investigation may be carried out by a person who is not a trained adult sexual assault investigator, but who is under the supervision of a trained investigator. We encourage the Police to ensure that, in all instances, the requirements of the ASA Investigation Guidelines are complied with.

2.76

The ASA Investigation Guidelines require an investigator to obtain permission from a Detective Senior Sergeant or above rank before suggesting or informing a complainant that the investigator believes that the allegation is fabricated.

Monitoring the implementation of the ASA Investigation Guidelines

Auditing

2.77

The Police have carried out two internal reviews to determine how many particular sorts of adult sexual assault cases are investigated by staff who have received specialist training in investigating adult sexual assault complaints.

2.78

In the first of the internal reviews (covering April 2008 to March 2009), the Police examined cases of alleged sexual violation by rape or unlawful sexual connection of females over 16, and indecent assault on males and females over 16. Of 120 files randomly selected from all 12 districts (10 from each district), 68 files or 57% were assigned to staff with specialist training in adult sexual assault investigation.

2.79

Specialist training in investigating adult sexual assault complaints is important for members of the Criminal Investigation Branch, because they investigate most complaints about adult sexual assault. Twenty-four percent of the files were assigned to staff who were not part of the Criminal Investigation Branch and only 10% of the assigned staff had received the specialist training.

2.80

In the second of the internal reviews, the Police examined 288 files, from all 12 districts, relating to cases of alleged rape or unlawful sexual connection of females. More than 90% of these cases were investigated by Criminal Investigation Branch staff. The Police found that 61% of these files had been investigated by staff with specialist training in investigating adult sexual assault complaints. A small percentage of files (8%) were assigned to staff who were not part of the Criminal Investigation Branch, and 36% of the assigned staff had received the specialist training.

2.81

At the time of our audit fieldwork, the Police intended to do a third audit in February 2010. Their intention was that, by 30 June 2010, 80% of investigated adult sexual assault cases will have been investigated by staff with the appropriate specialist training.

2.82

In December 2008, the Police decided, after an Adult Sexual Assault Policy Implementation Review, that "[adult sexual assault] files should be randomly audited by independent expert practitioners to ensure quality of decisions and outcomes". We were not made aware of any such independent scrutiny of files at the time of our audit fieldwork.

2.83

In our view, the Police need to conduct additional independent assessments of the implementation of the ASA Investigation Guidelines.

Dip sampling

2.84

The ASA Investigation Guidelines state that there should be annual "dip sampling" of completed adult sexual assault files to assess whether they have been completed in the approved manner. Dip sampling is a means of assessing whether selected expectations have been met, by looking at what has been recorded in the files.

2.85

At the time of our audit fieldwork, we were told that the Police do dip sampling of five files about every month from a district and would be reporting the results of that work to their Executive Committee in February 2010. The results of this dip sampling were not available to us at the time of our audit fieldwork and we were unable to form a view on its adequacy or effectiveness. We were told that the dip sampling would be based around 9-10 indicators of compliance with the ASA Investigation Guidelines.

Other monitoring

2.86

The ASA Investigation Guidelines state that each Police district’s adult sexual assault co-ordinator will report annually to the national adult sexual assault coordinator at Police National Headquarters on:

- any issues relating to compliance with these guidelines and connected training

- any initiatives, preventative measures, endeavours and developments that have proved successful in the investigation and area of [adult sexual assaults].

2.87

We have seen only limited historical evidence of this occurring. The Police told us that district adult sexual assault co-ordinator roles are filled mostly by district crime managers or non-commissioned officers with wide-ranging responsibilities from the Criminal Investigation Branch.

2.88

The Police do not appear to have sought additional dedicated funding from the

Government and Parliament for ensuring that their response to the Commission’s

recommendation R9 was effectively implemented.

Summary

2.89

The Police have updated their ASA Investigation Guidelines and reviewed some files of investigations into adult sexual assault complaints. In our view, the work falls short of ensuring that the implementation of the ASA Investigation Guidelines is effective.

| Recommendation 7 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police give enough attention and priority to monitoring and auditing of adult sexual assault investigations to ensure that all of these investigations fully comply with the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Guidelines. |

| Recommendation 8 |

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police conduct additional independent assessments of the implementation of the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Guidelines, to clarify whether complainants receive a consistent level of service (including when their complaint is first received) and whether the training and resources necessary to effectively implement the Investigation Guidelines are in place. |

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R10

New Zealand Police should incorporate the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Policy in the "Sexual Offences" section of the New Zealand Police Manual of Best Practice for consistency and ease of reference.

Our assessment: Completed by the Police.

2.90

The ASA Investigation Guidelines are incorporated within the "Sexual offences" chapter of the Police manual. This document can be accessed through the Police Intranet. Therefore, the ASA Investigation Guidelines are available to staff who have computer access to the Police Intranet.

2.91

The Police published the ASA Investigation Guidelines on the Police Intranet on 1 July 2009.

Summary

2.92

The ASA Investigation Guidelines are available to all staff with access to the Police Intranet.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R11

New Zealand Police should strengthen its communication and training practices by developing a system for confirming that officers have read and understood policies and instructions that affect how they carry out their duties and any changes thereto.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

Critical policies and instructions

2.93

The Police have set up an electronic notification and comprehension-testing tool, called "I-learn", for critical policies and instructions. It was new and not in widespread use at the time of our audit fieldwork.

2.94

Comprehension testing is required if the policy or instruction is considered "critical". The Police do not intend to test whether staff know and understand all Police policies.

2.95

There is much discretion in the process used to decide whether a policy or instruction is "critical". In our view, there is some prioritisation risk in this approach because it relies on a business owner (the person responsible) judging the importance of their area’s policy or instruction. They can do this without considering the relative importance of their policy or instruction against policies and instructions from outside their area, and in the absence of focused strategic oversight across areas.

2.96

The I-learn tool provides employees with a copy or link to a policy or instruction as well as testing their understanding of it. This means that, in effect, the tool is an "open book" test. I-learn records each candidate’s results, including the number of attempts and the questions that were answered correctly and incorrectly. Currently, the results of any other comprehension testing, and information about staff who have not completed the tests, would have to be manually collated.

2.97

The Police are working on an electronic link between I-learn and their PeopleSoft human resources database so that employee data can be transferred to I-learn, and results can be transferred to PeopleSoft.

Non-critical policies and instructions

2.98

The Police do not test how well staff understand policies and instructions that are not considered critical. Instead, the Police rely on employees taking responsibility for studying the documents, and the normal publishing and information-sharing processes. These processes may include:

- local district newsletters;

- specific training;

- information in the Ten One newsletter;

- information on the "Bully [bulletin] board";

- information in the Commissioner’s blog;

- direct email notification; and

- notification through the "what’s new" section of the Police instructions Intranet pages.

2.99

These processes may make it more likely that police officers have read and understood policies and instructions that affect how they carry out their duties, and any changes to them.

2.100

We encourage the Police to strengthen how they:

- identify the policies and instructions that affect how police officers carry out their duties;

- prioritise those policies and instructions according to significance;

- test and confirm that police officers understand those policies and instructions; and then

- use the results of that testing to improve the communications and training practices.

2.101

We consider that the ASA Investigation Guidelines would have to be high on the list of priorities and tested.

Summary

2.102

The Police have strengthened their communications and training practices. They have set up an electronic system that can test how well staff know and understand policies and instructions. They still have further progress to make to ensure that the system is used, at least for critical policies, and that communication and training practices are informed by the results.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R12

New Zealand Police should strengthen its communication and training practices to ensure the technical competencies of officers are updated in line with new policies and instructions.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.103

We described the Police’s approach to confirming that police officers have read and understood policies and instructions related to their duties in our assessment of progress against recommendation R11. We were not made aware of any other systems or processes for ensuring that technical competencies are updated for new policies and instructions.

2.104

The business owners of policies or instructions are responsible for identifying whether and how to update any corresponding technical competencies. They have a great deal of discretion, and the Police rely on the decisions they make. It is up to these business owners to advocate that training in updated technical competencies becomes part of the annually mandated national training.

2.105

In September 2009, the Police commissioned analysis to identify the specific duties that are carried out by general duties constables during the early years of their careers. The Police intend this work to help them to:

- write an accurate job description;

- define the essential technical and organisational competencies for the role; and

- better understand their current recruitment, selection, and training systems.

2.106

In our view, this work is useful for supporting the competency of employees to be current and relevant. This type of work should be programmed to occur relatively regularly, in the absence of other systems and processes. The work could also be extended to other ranks, although the risk of technical competencies being misaligned with new policies and instructions is perhaps greatest for frontline constables, given the breadth of the issues they deal with.

2.107

It is also vital that supervisors and sergeants are up to date with new policies and instructions and that they support the development of officers’ competencies accordingly.

Summary

2.108

The Police have a discretionary process for updating technical competencies in line with new policies and instructions. More work is required to meet the Commission’s recommendation.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R13

Bearing in mind the mobility of the workforce, New Zealand Police should conduct a review of what training should be mandatory at a national level and what should be left to the discretion of districts.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.109

The Police have carried out three reviews of aspects of training that have informed their approach to determining national and district training requirements. One of these reviews (November 2009) examined district training. The others (September 2009 and November 2009) examined the Police’s training system and the structure and role of the Training Service Centre (the Royal New Zealand Police College).

2.110

The reviews found that district training activities were not integrated with national training, and that national planning and processes to control the volume and type of training in the districts were poor. They also found a significant gap in the effectiveness of evaluation, which was not necessarily ensuring that training was delivered properly. The Police were not able to demonstrate that knowledge gained through training was applied in the workplace or that behaviour was changing.

2.111

As a result of these reviews, the Police said that they would take a more centralised approach to district and national training, with enough oversight and control to maximise effectiveness and efficiency. This would involve the Executive Committee approving an annual training delivery plan based on advice from the Police’s Training Advisory Committee. The annual training delivery plan specifies which training should be mandatory, takes into account the Police’s annual operational and strategic priorities for a given year, and considers feedback from district commanders.

2.112

The Police’s Training Governance Committee (now the Training Advisory Committee) has decided that training should be limited to 5% of annual working hours, which means about 80 hours each year. Half of this could be for "cyclic" and nationally mandated training. The other half is for training that is left to the discretion of districts.

2.113

In 2010/11, there will be further significant changes to the process for deciding on, delivering, and evaluating mandatory training under the Training Service Centre change programme.

2.114

Eventually, the quality and content of all training provided by Training Service Centre staff both at the Royal New Zealand Police College and in districts will be subject to approval by an Approvals Committee.

Summary

2.115

The Police have reviewed aspects of national and district training and have set up an annual process for determining national training requirements. The Police are still making significant changes to their systems and processes for planning, delivering, and evaluating their training. There is still work to do to complete the Commission’s recommendation and check that the changes are having the desired effect.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R14

New Zealand Police should ensure that the practice of providing investigating officers with a reminder of the standards for complaint investigation is applied consistently throughout the country.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.116

To start an investigation, the Professional Standards team at Police National Headquarters writes to the relevant district commander requesting that an investigation start. For serious complaints, this letter requests that the district commander ensure that:

- a declaration under the Conflict of Interest Policy is completed;

- the investigator maintains regular liaison with the Independent Police Conduct Authority investigators;

- the investigator maintains regular contact with the complainant;

- an investigation plan is prepared in consultation with the National Manager, Professional Standards;

- the investigator, Police staff, and witnesses are aware that this matter is a Police investigation and that the normal Bill of Rights and disclosure rules apply; and

- separate investigators are appointed to conduct the criminal investigation, employment investigation, and review of policy, practice, and procedure.

2.117

The actual standards of investigation are outlined in a document entitled Police investigations of complaints and notifiable incidents. This is available on the Police Instructions Intranet site.

2.118

We did not see any practices for providing the police officers carrying out the investigation with a reminder of the standards for complaint investigation.

2.119

Without a system for checking, the Police will not know whether the recommendation has been met.

Compliance with standards

2.120

The Police have several review processes that can involve checking whether police officers have complied with investigation standards.

2.121

The Police told us that they use a former police inspector, a District Court judge, a former police officer, and a former detective superintendent to provide an external review function for significant complaints files (estimated at about 10 reviews a week), before the files are returned to the Independent Police Conduct Authority. The Police also told us that the Professional Standards team at Police National Headquarters provides "checks and balances" to ensure that investigations are carried out consistently.

2.122

We were told that checks at the Police National Headquarters included a review of files to examine:

- the correct recording and notification of complaints;

- whether Police have met their obligations to the complainant;

- whether completed complaint enquiry files show that procedural requirements and enquiry avenues have been completed in the appropriate manner (and, if not, identify the discrepancies and direct remedial action);

- whether district investigations reach the national standards; and

- whether summaries and recommendations from investigating officers and district managers are consistent with the recorded facts.

2.123

The Police also have three groups ("pods") at Police National Headquarters, each with responsibility for a geographic area and covering the whole country in total. These groups scrutinise files to ensure that they are completed properly before the files go to the Independent Police Conduct Authority. The Police told us that the groups are responsible for:

- ensuring that the appropriate disciplinary option or remedial action is recommended where evidence discloses misconduct or neglect of duty;

- co-ordinating and implementing suspension, diversion, duty stand-down, and dismissal processes;

- preparing correspondence where the Independent Police Conduct Authority has commented on a police officer’s conduct, the conduct of an investigation, or some other matter relating to practice, policy, and procedure; and

- ensuring that the Police comply with obligations under the Policing Act 2008, the Victims of Offences Act 2002, and the Independent Police Conduct Authority Act 1988.

Summary

2.124

The Police have written expectations available to all staff to guide investigations of complaints against Police. They also do some checking of complaint investigation files. However, they are not able to determine whether the processes are effective in providing an adequate and nationally consistent reminder of the standards required for investigators.

2.125

We encourage the Police to put in place monitoring measures to check that the practices used to provide investigators with a reminder of the standards for complaint investigations are applied consistently and are effective.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R15

New Zealand Police should improve the process of communicating with complainants about the investigation of their complaint, particularly if there is a decision not to prosecute. Complainants and their support people should be given: realistic expectations at the start of an investigation about when key milestones are likely to be met; the opportunity to comment on the choice of investigator; regular updates on progress, and advance notice if the investigation is likely to be delayed for any reason; assistance in understanding the reasons for any decision not to prosecute.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.126

The ASA Investigation Guidelines state that:

… providing information to victims about the processes being undertaken and explaining reasons why actions are necessary is one of the most important factors in ensuring a victim’s welfare and pathways to recovery.

2.127

The ASA Investigation Guidelines require investigators to keep complainants well informed about the investigation of their complaint from early on in the process. This includes providing information about:

- the timing of each stage of the investigation process;

- the progress of the investigation; and

- any decision not to proceed with an investigation or prosecution.

2.128

The ASA Investigation Guidelines also require the Police to give a complainant an opportunity to comment on their needs for the selection of the:

- adult sexual assault investigator;

- specialist adult witness interviewer;

- medical/forensic doctor; and

- support person(s).

2.129

Police officers have to record the contact they have with complainants to provide progress updates about and during the investigation. To record the contact, they are required to use a Police Record of Victim Contact form, or POL1060. We were told that the Police have found instances where police officers have had contact with complainants but have not documented that contact on the form.

2.130

We were not made aware of any plans for assessing how well the requirements in the ASA Investigation Guidelines are applied or working beyond any aspects of communication with complainants that may be examined as part of dip sampling (see paragraphs 2.84-2.85). The Police told us that contact with the complainant would be one of the dip sampling indicators.

Summary

2.131

The Police have identified the importance of good communication with adult sexual assault complainants. But more work is required to ascertain how well complainants are kept informed and whether the communication requirements in the ASA Investigation Guidelines need to be modified.

| Recommendation 9 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police regularly assess whether adult sexual assault complainants are kept well informed during the Police’s investigation of their complaints. |

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R16

New Zealand Police should develop a consistent practice of identifying any independence issues at the outset of an investigation of a complaint involving a police officer or a police associate, to ensure there is a high degree of transparency and consistency. The practice should be supported by an explicit policy on the need for independence in such an investigation. In respect of the handling of conflicts of interest, the policy should, among other things, identify types and degrees of association; define a conflict of interest; provide guidelines and procedures to assist police officers identify and adequately manage conflicts of interest (including in cases where cost or the need for prompt investigation counts against the appointment of an investigator from another section or district); ensure that the risk of a conflict of interest involving investigation staff is considered at the outset of any investigation involving a police officer or police associate.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.132

The Police’s Independence of Investigations (Safe Processes) document provides high-level guidance to help police officers to identify conflicts of interest and specific requirements. It requires any conflict to be declared to the officer’s supervisor. The guidance notes that "under no circumstances must supervisors investigate allegations of sexual serious misconduct by Police employees under their direct supervision."

2.133

In instances where it is necessary to act immediately to protect life, property, or the public peace, Police employees must act to properly discharge their lawful duties and subsequently declare any conflicts of interest to an appropriate supervisor. The supervisor must document what has been declared, determine what affect the conflict had on the actions taken by the employee, and act on this determination accordingly.

2.134

The Independence of Investigations (Safe Processes) document requires police officers to complete a conflict of interest declaration for investigations into matters considered to be in categories 1-3 using the Independent Police Conduct Authority’s categorisation of complaints.6 The investigator’s supervisor has to review and sign the declaration.

2.135

The guidance does not require a conflict of interest declaration for matters that fall within categories 4-5 (see below). Nevertheless, in our view, ensuring independence in the investigation of these is still very important, especially given matters such as excessive delay, or failing to act in good faith, have the potential to escalate into a more serious matter.

2.136

Category 4 complaints are defined as those that are appropriate for conciliation. They include, for example, excessive delay, inappropriate racial comments, serious discourtesy, minor policy breaches and minor traffic matters, and inappropriate use of any Police information system not amounting to corruption.

2.137

Category 5 complaints are defined as minor or older than 12 months at the time of reporting and have been declined by the Independent Police Conduct Authority but may still be of interest to the Police. Examples include attitude or language complaints, failing to act in good faith, and where the person aggrieved does not make a formal complaint.

2.138

In our view, investigations into complaints that fall within categories 4-5 could benefit from scrutiny from someone beyond the prevailing culture of a police officer’s immediate work group. There is the potential for complaints investigated by someone within the same work group to be poorly assessed if it was the same prevailing culture that led to, or condoned, the behaviour in the first place.

2.139

Recommendation R16 called for consistent practice in identifying conflicts of interest at the outset of an investigation. We encourage the Police to require investigators investigating any complaint against a police officer to complete a conflict of interest declaration – regardless of the seriousness of the complaint.

Summary

2.140

The Police’s guidance notes the need for independence when investigating complaints, and also applies to complaints involving a police member or associate. The Police need to do more to ensure that conflicts of interest are consistently and routinely identified at the start of any investigation into a complaint involving a police member or associate.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R17

New Zealand Police should expand the content of its ethics training programme to include identifying and managing conflicts of interest, particularly in respect of complaints involving police officers or police associates.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.141

The Police’s training on Contemporary Policing in New Zealand (which covers discretion, ethics, and professionalism) includes a relatively small section about conflicts of interest. The section highlights the need to recognise when a conflict of interest exists (real or perceived). The section also refers to conflicts of interest policy (see our assessment of progress with recommendation R16 for more information about this).

2.142

The facilitator’s guide for the training does not pay particular attention to complaints involving police members or associates.

2.143

The Police told us that, as of February 2010, they were reviewing training packages to include identifying and managing conflicts of interest, particularly how complaints against police members or associates might be incorporated into their training.

2.144

We encourage the Police to complete this work and to monitor its effect on the extent to which police officers can identify and manage actual or perceived conflicts of interest involving a colleague or associate.

Summary

2.145

The Police include conflicts of interest in the Contemporary Policing in New Zealand training, but the training does not give particular attention to complaints involving police members or associates. The Police are yet to identify how they will incorporate complaints involving police members or associates into their training.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R18

New Zealand Police should ensure that training for the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Policy is fully implemented across the country, so that the skills of officers involved in sexual assault investigations continue to increase and complainants receive a consistent level of service.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

Training in investigating adult sexual assault complaints

2.146

The ASA Investigation Guidelines give the Criminal Investigation Branch responsibility for adult sexual assault investigations. The Police have estimated that there are 700-800 Criminal Investigation Branch members who could be "directly dealing with, or could be called upon to deal with, [adult sexual assault] investigations".

2.147

The Police have a specialist five-day training course in investigating adult sexual assault complaints. The adult sexual assault investigators’ course ran in seven districts in 2007/08, in five districts in 2008/09, and at the Royal New Zealand Police College in both years. In 2009/10, the course has been delivered in three districts and at the Royal New Zealand Police College (as of 27 November 2009). At the time of our audit fieldwork, further courses were scheduled and some additional courses had been approved but not yet scheduled.

2.148

In 2007/08, 292 staff attended the adult sexual assault investigation training course. From 1 July 2009 to 27 November 2009, 82 staff attended the adult sexual assault investigation training course. The Police scheduled and approved a further 288 training places for the remainder of the 2009/10 financial year.

2.149

The Police’s priority has been to have the staff most likely to investigate adult sexual assault undergo the adult sexual assault investigation training course. The Police envisage that, after three years, all of the relevant Criminal Investigation Branch staff will have received training in adult sexual assault investigations.

2.150

A record of who had booked and completed the training is kept in the Police’s PeopleSoft human resources system.

2.151

Supervisors are responsible for ensuring that staff attend the training. District commanders are responsible for making sure that they have enough trained and qualified staff for specialist investigations and interviews to satisfy local demand.

2.152

Information on the completion rates for adult sexual assault investigation training in one of the districts we visited is provided in Figure 3, analysed by unit. In summary, fewer than 40% of the district’s staff identified by the Police as needing training in investigating allegations of adult sexual assault had received that training. This varied between units, from no staff having been trained to all staff having been trained.

2.153

In another district we visited, 14 of the 17 Criminal Investigation Branch staff in one provincial centre had been trained. This further illustrates the variation in training coverage between teams and areas.

2.154

We acknowledge that providing training for all of the staff who investigate adult sexual assault complaints will take time and needs to be carefully scheduled so that it does not detract from the Police’s delivery of services to the public. But the training needs to happen.

2.155

There is some evidence that sworn staff do not treat the training as a priority. In 2008/09, district training sessions had to be cancelled on four occasions. This is a waste of resources in terms of time spent organising these sessions as well as a lost training opportunity.

Figure 3

Number of staff, in one district, trained and still to receive specialist training in

investigating adult sexual assault complaints

| Unit | Trained before 2007 | Trained in or after 2007 | Total | Still to be trained | % trained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 100% |

| CIB Break Squad | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 46% |

| CIB Car Squad | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 67% |

| CIB Child Abuse Team | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 50% |

| CIB Drug Squad | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0% |

| CIB Fraud Squad | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 44% |

| CIB Proceeds of Crime | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 33% |

| Combined Investigation Unit | 7 | 43 | 50 | 78 | 39% |

| Crime services | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 13% |

| Crime Strategy Group | 3 | 2 | 5 | 31 | 14% |

| Criminal Intelligence Section | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 33% |

| District Crime | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 50% |

| Organised Crime Unit | 1 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 38% |

| Patrol and Response | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 100% |

| Section | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 100% |

| Total | 17 | 74 | 91 | 154 | 37% |

CIB: Criminal Investigation Branch.

Source of raw data: New Zealand Police.

2.156

In December 2008, in the Adult Sexual Assault Policy Implementation Review, the Police recommended that a "reserves pool should be maintained to ensure [Adult Sexual Assault Investigation] 5 day training spaces are not wasted through late withdrawals". We support such an approach.

2.157

At the rate of progress to date, it will be some time before all of the staff who investigate adult sexual assault complaints have attended the training course.

2.158

We also note that the Commission’s expectation was that the skills of officers involved in adult sexual assault investigations would continue to increase. Therefore, even when all of the relevant staff have been through the current adult sexual assault investigation training course, recommendation R18 will not have been fully completed until the Police have planned for continuing increases in the skills of police officers involved in adult sexual assault investigations. One of our interviewees acknowledged that, even at this stage, there could be currency issues with the training and that a refresher might be needed.

Consistent levels of service

2.159

We decided that we would not directly contact adult sexual assault complainants. Instead, we spoke with an umbrella group of agencies that provide specialist support services to sexual assault complainants.

2.160

As part of our audit, we met with members of Te Ohaaki a Hine – National Network for Ending Sexual Violence Together (TOAH-NNEST). The information we have obtained through our discussions with TOAH-NNEST includes individual perceptions. This information is important because perceptions influence people’s behaviour and their expectations of, interactions with, and confidence in, the Police.

2.161

We were told that there is wide variation in complainants’ experiences of the Police and that this largely reflects whether the police officers have been trained adequately, and the varying abilities, attitudes, and commitment of the police officers involved. We were also told that as well as this variation within Police districts, there is also considerable variation in police officers’ attitudes and service to complainants between Police districts.

2.162

TOAH-NNEST told us that there are some excellent police officers doing great work in investigating adult sexual assault complaints. They also told us about a number of recent examples where complainants have had bad experiences with the Police and this, in TOAH-NNEST’s view, has led to further victimisation of the complainants.

2.163

In our view, such large variations in complainants’ experiences would be reduced if the ASA Investigation Guidelines were followed, investigators were trained, and training was effective.

Citizens’ satisfaction survey

2.164

The Police carry out an annual citizens’ satisfaction survey of people who have had contact with the Police in the previous six months. In 2008/09, 9821 people were interviewed. The survey included a question about why people contacted the Police. The prompts for responses include the option of "An assault (including sexual)", but the Police told us that the survey sample includes very few responses from victims of a sexual assault.

2.165

The survey findings suggest that the experiences of people who had contact with the Police about an assault are not consistent, and – compared with others who had contact with the Police on other matters – their experiences are generally more negative. In our view, all people in contact with the Police should be able to expect and receive consistent service from the Police.

Generic investigative interviewing

2.166

Separate from the specialist adult sexual assault investigation training, the Police have four levels of training available in specialist interviewing. The third level covers sexual assault and police officers trained to this level should, ideally, be involved with interviewing the victims of a sexual assault. The fourth level is a specialist advisory level.

2.167

The Police’s December 2008 review of the implementation of the ASA Investigation Guidelines noted that ideally all adult sexual assault interviews should be conducted by staff trained to level three (and workloads allocated accordingly). We have not sought quantitative information on the extent to which this ideal is being met, but we were told that the Police do not yet have dedicated specialist interviewers or enough interviewers trained to level three. The Police also told us that good investigative interviewing can save court time and file preparation time.

2.168

One of the barriers to better interviewing is the lack of suitable facilities for interviewing victims and witnesses. We were told that police stations are generally designed for interviewing alleged offenders rather than victims or witnesses. We were also told that there are financial barriers to having more suitable facilities available.

2.169

Through the December 2008 review of adult sexual assault investigations, the Police have recommended that interviewers trained to level three (regardless of the nature of the interview) and other staff working predominantly on adult sexual assault cases should have a scheduled visit with a psychological service every six months. This is for the well-being of the staff involved. In our view, this is a positive step that the Police have taken.

Initial complaint action

2.170

The Police also train staff in the initial action to take when receiving an adult sexual assault complaint. This training is aimed at watchhouse, reception, communication centre, and frontline staff who may be the first people to have contact with a complainant. The training is part of the training for recruits and part of the annual mandatory training. The Police’s review of this training, as part of the review in December 2008, concluded that the training:

- varies in length and quality of training delivery

- should be monitored to identify competency of trainer and ensure value is obtained by attendees

- should be delivered to all watchhouse and relevant frontline staff.

Reviews of training

2.171

The same review recommended that:

… a review of all [adult sexual assault-related] training should be conducted to determine whether it is relevant, necessary and achieves outcomes.

2.172

We agree that such a review would be beneficial because of the:

- apparent ongoing disruption of scheduled training by operational priorities and annual leave; and

- the Police’s review of the implementation of the Adult Sexual Assault Investigation Policy, which raised questions about the quality of training.

2.173

In November 2009, the Police conducted a review of district training. The review included seeking feedback from focus groups about all training (not just adult sexual assault investigation training). The Police report that investigative interviewing and adult sexual assault investigation were identified as good training experiences.

2.174

We encourage the Police to conduct a review of all training, as recommended by the Police’s Organisational Assurance Group in November 2009, to determine whether the training is relevant, necessary, and achieves the expected outcomes. The review should include adult sexual assault investigation training and initial complaint action training.

Summary

2.175

The number of police officers who have participated in adult sexual assault investigation training continues to increase but not all staff involved in adult sexual assault investigations have received the training. The Police do not have any specific plans for periodically measuring or assessing complainants’ experiences beyond the citizens’ satisfaction survey, nor any plans for continuing to increase the skills of staff involved in adult sexual assault investigations.

| Recommendation 10 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Police devise an approach for ongoing skills development in adult sexual assault investigations beyond the life of the current adult sexual assault investigation training course. |

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R19

New Zealand Police should initiate cooperative action with the relevant Government agencies to seek more consistent Government funding for the support groups involved in assisting the investigation of sexual assault complaints by assisting and supporting complainants.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.176

The Police have identified three types of support that should be available to adult sexual assault complainants:

- crisis support;

- the Sexual Abuse Assessment and Treatment Service; and

- victim safety and offender accountability support.

2.177

The three types of support rely on co-operative relationships with support agencies, and collectively are called the "tripartite response".

Crisis support

2.178

Support for adult sexual assault complainants is provided by specialist providers. Victim Support provides support when specialist providers, such as Rape Crisis, are not available. (In 2006, the Police estimated that specialist providers were not available in about a third of cases.) Victim Support is a community organisation, present in more than 70 locations, that supports people affected by crime and other trauma. It is an independent charitable trust that works closely with the Police, but it is not a provider of specialist adult sexual assault support services.

2.179

In one of the provincial centres we visited, the Police call Rape Crisis for every complaint of adult sexual assault. In another of the centres we visited, there is no specialist support service available and complainants receive support from Victim Support instead.

Sexual Abuse Assessment and Treatment Service

2.180

The Sexual Abuse Assessment and Treatment Service (SAATS) is a medical forensic service for all victims of sexual abuse (women, men, children, and adolescents). It provides triage, assessment, treatment, and referral services. The service is available irrespective of whether the person has chosen to make a complaint of sexual assault to the Police or not.

2.181

District health boards have contracts with the providers of SAATS services. The services are provided by specially trained doctors, nurses, and paediatricians who belong to an incorporated society – Doctors for Sexual Abuse Care Incorporated (DSAC). DSAC is also a member of TOAH-NNEST.

2.182

The Police told us that they participated in the development of the SAATS model from its beginning. Specifically:

In late 2006, Police Commissioner Broad met with the CEO’s [sic] of [the Accident Compensation Corporation] and [the Ministry of Health] and from that meeting it was decided that [the Accident Compensation Corporation] would lead a project to develop a sustainable funding model, thereafter named SAATS. A working group was set up with representatives from the three agencies as well as District Health Boards (DHBs) and subject matter experts from DSAC and Police Medical Officers (PMOs). A service model and service specifications were developed.

From this early date, [the Accident Compensation Corporation] (via Police) were meeting service costs with interim payments for Doctors providing the on-call service and Police looked to increase and make consistent the hourly rates for service provision.7

2.183

We were also told that, in one of the areas we visited, there are now good local rosters of facilities and DSAC doctors available, and this has reduced the need for victims to travel long distances.

Victim safety and offender accountability support

2.184

The Police are responsible for victim safety and offender accountability support, which means providing "safe" facilities for examining and interviewing complainants and ensuring that investigations are carried out properly. Two Police districts, Auckland and Counties Manukau, have dedicated adult sexual assault investigation teams. In all other districts, generalist Criminal Investigation Branch investigators carry out the investigations into adult sexual assault complaints.

2.185

The tripartite response is still relatively new. Since November 2008, district commanders have had to ensure that local agreements are in place outlining the relationship between local tripartite partners.

Funding

2.186

In July 2009, TOAH-NNEST, the Government’s partner in the Taskforce for Action on Sexual Violence (the Taskforce), recommended to the Minister of Justice that dedicated resources should be available specifically targeted at activity to better prevent and respond to sexual violence. Developing sustainable funding models is a priority for TOAH-NNEST. The Government’s response to the Taskforce’s recommendations (set out in Te Toiora Mata Tauherenga Report of the Taskforce for Action on Sexual Violence) was not available at the time of our audit fieldwork. The Commissioner of Police was a member of the Taskforce.

2.187

SAATS services are jointly funded by the Police, the Accident Compensation Corporation, and the Ministry of Health (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Funding model for Sexual Abuse Assessment and Treatment Service

2.188

The Police meet a proportion of SAATS fees through funding from Police National Headquarters. Police districts will pay for medical examination kits, deposition writing, and other aspects of SAATS services, as agreed in local service level agreements. There is, therefore, the potential for some geographic variation in the arrangements in place and the services that are available.

2.189

SAATS does not fund crisis support.

Summary

2.190

The Police participate in a "tripartite" response to provide support services for adult sexual assault complainants. The Police contribute funding for SAATS services. This does not include funding for crisis support services. Specialist crisis support services are not yet available in all regions. Funding for specialist crisis support services depends, to an extent, on the Government’s response to Te Toiora Mata Tauherenga Report of the Taskforce for Action on Sexual Violence.

Commission of Inquiry’s recommendation R20

In relation to investigations of sexual assault complaints against police officers or police associates, New Zealand Police should have in place systems that: verify that actual police practices in investigating complaints comply with the relevant standards and procedures; ensure the consistency of such practice across the country, for instance in the supervision of smaller and rural stations; identify the required remedial action where practice fails to comply with relevant standards; monitor police officers’ knowledge and understanding of the relevant standards and procedures.

Our assessment: Not yet completed by the Police.

2.191

We described the processes the Police intend to use to monitor the implementation of the ASA Investigation Guidelines in our assessment of the Police’s progress against recommendation R9.

2.192

The Police told us that, in their view, complaint investigations are open to scrutiny through the file review processes.

2.193