Part 5: Case studies

5.1

This Part sets out five case studies that show the complexities arising from the number of public entities involved in the recovery. The case studies show how the earthquakes have affected the lives of many Cantabrians. For each case study, we describe:

- what happened;

- the roles and responsibilities of public entities involved;

- the costs and funding arrangements for the public sector; and

- the effect on residents.

5.2

The five case studies are about:

- repairing and rebuilding roads, water supply, stormwater systems, and wastewater systems (horizontal infrastructure);

- redeveloping the Christchurch CBD;

- the Government's red zone offer;

- damaged properties in TC3 areas; and

- managing risks to homes in the Port Hills.

Case study 1: Repairing and rebuilding horizontal infrastructure

What happened?

5.3

Roads, water supply, stormwater systems, and wastewater systems (known as horizontal infrastructure) suffered severe damage in the earthquakes, affecting many residents and causing localised environmental damage.

5.4

There are estimates that 1021 kilometres of roads in Christchurch need rebuilding (52% of urban sealed roads in Christchurch), 124 kilometres of water supply mains in Christchurch were damaged, and about 528 kilometres of Christchurch's sewerage were badly damaged (about a third of the total sewerage in Christchurch).50

5.5

The repair and rebuilding of horizontal infrastructure is under way and expected to take about five years to complete. This is a complex and challenging task because many of the infrastructure systems are underground, making damage assessment and designing repairs and replacements difficult.

5.6

The challenges and risks to repairing and rebuilding the horizontal infrastructure include:

- integrating work to repair the horizontal infrastructure with the wider Recovery Strategy;

- being able to sequence and prioritise the horizontal infrastructure work and ensure that the work is carried out in the most efficient and cost-effective way;

- connecting horizontal infrastructure to new residential subdivisions and core services (such as schools and medical facilities); and

- managing and sharing the cost of the repairs between local and central government.

Who is responsible for what?

5.7

CCC, Waimakariri District Council, and Selwyn District Council own most of the horizontal infrastructure damaged in the earthquakes. NZTA is responsible for national highways and for repairing damaged highways.

5.8

The horizontal infrastructure rebuilding is being carried out differently in each district. Waimakariri District Council and Selwyn District Council have separate contracts with construction companies to carry out infrastructure recovery projects in their districts.

Stronger Christchurch Infrastructure Rebuild Team

5.9

In Christchurch, about 85% of the damaged horizontal infrastructure is being repaired and rebuilt through the SCIRT alliance arrangement with five construction companies, in partnership with CCC, CERA, and NZTA (see Figure 8). The five construction companies are City Care Limited (owned by CCC), Downer New Zealand Limited, Fletchers, Fulton Hogan Limited, and McConnell Dowell Construction Limited.

5.10

CCC, CERA, and NZTA set up SCIRT to manage the large volume of repairs and building projects required throughout Christchurch – to provide a way of controlling cost inflation, to fast-track repairs, and to ensure that work done is of high quality.

5.11

An alliance arrangement is normally used in complex and high-risk infrastructure projects, where risks are often unpredictable and best managed collectively. For example, NZTA uses alliances for several large roading projects. However, an alliance of this size and complexity, covering multiple projects, is unusual in New Zealand.

5.12

SCIRT is complex because it has three clients – CCC, CERA, and NZTA. The alliance carries out wide-ranging work made up of multiple projects that directly affect the lives of residents because of the disruption that the repairs cause, including road closures, extensive road works, noise, and dust. Residents will observe many different contractors carrying out repairs and causing disruption to their lives. It is important for residents to understand where, when, for how long, and why this disruption will happen, to help them to accept and deal with disruption.

Figure 8

Responsibility for repairing and rebuilding roads, water supply, stormwater systems, and wastewater systems in greater Christchurch

5.13

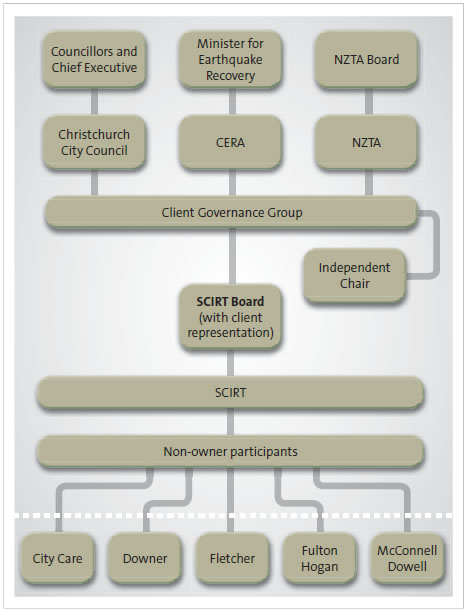

SCIRT has governance and oversight arrangements to provide guidance and to monitor the delivery of the infrastructure programme in Christchurch. Figure 9 shows how the alliance is governed.

Figure 9

The Stronger Christchurch Infrastructure Rebuild Team's description of its governance arrangements

Source: Stronger Christchurch Infrastructure Rebuild Team.

5.14

The Alliance General Manager – whose role is similar to that of a chief executive – manages SCIRT day to day. SCIRT has a board that is responsible for providing direction to the Alliance General Manager. The board is made up of eight executive managers (one from each participating public entity and construction company) and is responsible for ensuring that the alliance achieves the desired outcomes.

5.15

A Client Governance Group – whose members are managers from the three public entities – provides direction to the SCIRT board. The Client Governance Group has an independent chairperson (appointed by the Minister) and is supported by:

- SCIRT's scope and standards review team, which sets standards and confirms the scope (where required);

- the strategy reference group, which provides strategic direction to the programme (including keeping it in line with the Recovery Strategy); and

- the funding team, which works out and monitors how the work is paid for – recommending processes and controls to ensure that funds are used in the most efficient way and that apportioning is in line with the cost-sharing policy.

The costs and funding arrangements

5.16

Because the condition of the below-ground assets (such as water pipes) has not been completely assessed, the estimate of the cost of the repair and rebuilding of horizontal assets is highly uncertain. The condition assessment, which is expected to be completed in 2013, will provide data for a more certain estimate of cost.

5.17

Because of the decisions to assign certain residential properties to the red zone, infrastructure needs in greater Christchurch differ from what much of the current infrastructure was designed for. Many decisions on the future design and configuration of horizontal infrastructure and services remain to be made. Until these decisions are made, estimates of cost will remain uncertain. The cost of maintaining temporary infrastructure is also significant.

5.18

CCC's latest estimate of the cost of infrastructure rebuilding is $1.9 billion.51 Waimakariri District Council's 2012-22 long-term plan disclosed about $46 million of projected expenditure (operating and capital expenditure) to repair and rebuild horizontal infrastructure assets.52 Almost half of Waimakariri District Council's costs were forecast to be incurred by 30 June 2012.

5.19

In contrast, the estimated damage to Selwyn District Council's horizontal assets is much less. The Council's 2010/11 annual report disclosed about $4 million of damage.53

5.20

The combined cost to the three local authorities of repairing horizontal assets is estimated to be nearly $2 billion, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10

Forecast cost of repairing or rebuilding horizontal infrastructure assets

| Asset | $million |

|---|---|

| Local roads | 1,023.5 |

| Wastewater/sewerage | 718.6 |

| Water supply | 143.8 |

| Stormwater | 72.5 |

| Total | 1,958.4 |

5.21

Insurance or Crown funding will meet much of the forecast cost to repair or rebuild horizontal infrastructure. However, the three local authorities are required to fund a large proportion.

5.22

Figure 11 shows that repairing horizontal infrastructure is expected to cost local authorities about $513 million. This cost is outlined in the local authorities' respective planning documents as well as the local authorities' individual proposals to fund the repair.

Figure 11

Sources of funding for the forecast cost of repairing horizontal infrastructure assets

| $million | ||

|---|---|---|

| Forecast cost to repair or rebuild | 1,958.4 | |

| Central government funding | 1,266.8 | |

| Insurance | 179.1 | |

| 1,445.9 | ||

| Balance to be funded by local authorities | 512.5 |

5.23

Local authorities are billed for the repair and rebuilding of horizontal infrastructure when contractors carry out the work. It is then up to the local authority to recover funds from other sources (that is, roading costs from NZTA for its contribution to the repair of local roads; funding from the Crown for restoring water, stormwater, and sewerage infrastructure; and recoveries from insurance companies). This will continue during the entire recovery.

5.24

Under this model, local authorities have to first incur the spending. The costs to date have been significant. For example, initial emergency response works and setting up SCIRT, including building the SCIRT office, cost CCC about $70 million. CCC will recover some of this from CERA and NZTA as project overheads, but it is estimated that this will take five years.

5.25

Each month, CCC incurs direct costs to pay for the repairs and rebuilding that SCIRT has done. The Council is funding a significant proportion of these costs through borrowing. This puts significant onus on the Council to manage the initial cashflow requirements of the horizontal infrastructure work. Up to May 2012, CCC had incurred $798.7 million of response and recovery costs. It had received $266.3 million from the Crown.

5.26

The Guide says that it is normal procedure for CCC to spend first and lodge a claim later. However, the Guide's drafters may not have envisaged damage of the size and scale in greater Christchurch. CCC has asked for an advance allocation of funding from NZTA and CERA based on a cost-allocation model so that CCC pays 40% of the costs and NZTA and CERA each pay 30%.

What is the effect on residents?

5.27

Many residents in earthquake-affected areas do not receive the same level of service they received before the earthquakes. Most of the repairs and reconstruction of infrastructure require digging up roads, which causes further disruption to traffic and services. The disruptions and delays in receiving these services could continue for a long time.

5.28

Community groups have sought good communication about the progress of the horizontal infrastructure work. Many people told us that SCIRT was a positive example of providing good communication.

Case Study 2: Redeveloping the Christchurch central business district

What happened?

5.29

The earthquakes badly damaged Christchurch's CBD. Nearly all the businesses in the CBD were displaced, and about 1000 buildings will be demolished and many others will require substantial repair. The CBD's horizontal infrastructure was badly damaged.

5.30

After the February 2011 earthquake, cordons were set up around central Christchurch. Properties were assessed to work out which buildings were unsafe and had to be demolished. Since then, CERA has been gradually reducing the size of the cordoned area as streets are made safe.

5.31

CERA and CCC have also supported initiatives such as the Cashel Mall Restart project to encourage people to use the centre of the city and to help attract businesses and investors back into the CBD when the rebuilding begins.

Who is responsible for what?

5.32

Under the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act, CCC was responsible for preparing a draft central city recovery plan for ministerial approval. CCC prepared the plan in partnership with CERA, Environment Canterbury, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and gave it to the Minister in December 2011 (see paragraph 2.56). The plan is in two volumes. Volume 1 contains the overall vision for the new CBD, and Volume 2 sets out proposed regulatory changes to CCC's city plan (a district plan under the Resource Management Act) to achieve the vision outlined in Volume 1.

5.33

Five principles that CCC said would create a vibrant and prosperous city guided this initial central city plan. These principles were to:

- foster business investment;

- respect the past;

- take a long-term view;

- have a city that was easy to get around; and

- foster vibrant central city living.

5.34

In April 2012, the Minister announced that he had asked that the powers under the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act be used to set up CCDU within CERA to effect the Recovery Plan and to take overall responsibility for redeveloping the CBD.

5.35

CCDU has roles in planning what the new CBD will look like, working with developers, and encouraging businesses to return to the CBD. The first task of CCDU has been to prepare a "blueprint" plan for significant building projects "anchor projects" which includes their location in the CBD.

5.36

CCDU appointed Boffa Miskell Limited as a lead company in a consortium to prepare the blueprint, which was published at the end of July 2012 (see paragraph 2.57). Boffa Miskell has worked with CCDU, the Council, and other organisations to prepare the blueprint, which outlines how central Christchurch will grow and provides direction for the Recovery Plan, of which it is a part.

5.37

CERA, through CCDU, is involved in many relationships that are critical to the success of the Recovery Plan. These include relationships with:

- CCC, which is likely to be responsible for managing many of the facilities and amenities proposed in the Recovery Plan;

- private sector investors, whose investment will be needed for the Recovery Plan to be realised;

- owners of land that CERA will need to buy so that the Recovery Plan can be put into effect;

- Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, as a strategic partner to the Recovery Plan;

- public entities that will move their offices and services back into the CBD; and

- the people of Christchurch, who will use the new CBD and have views on how it should take shape.

Costs and funding arrangements

5.38

The cost of creating a new CBD is still to be worked out. It will include a significant contribution from central government, a contribution from CCC, and investment from the private sector. Public entities will build and own some of the new buildings and amenities in the CBD (such as the Convention Centre and Town Hall).

5.39

CCC told us that it had spent a lot of time on the Recovery Plan before presenting it to the Minister in December 2011. However, the costs of preparing it have not been quantified.

5.40

CERA received an increase in appropriations in the 2012 Budget to set up CCDU and to put the Recovery Plan into effect.

What is the effect on residents?

5.41

The lack of a functioning CBD has had a significant effect on the residents of Christchurch. Since the February earthquake, Christchurch has not had a central commercial, cultural, or social centre. Services, amenities, and resources such as the Central Library and Arts Centre have not been available. This has affected the city's identity and is a daily reminder of the extent to which the earthquakes have affected those who live in and use the city.

Case Study 3: The Crown's offer to buy properties in the residential red zone

What happened?

5.42

The earthquakes caused extensive land damage throughout Canterbury, and some areas were particularly badly affected. After the earthquakes, CERA zoned land in the earthquake-affected areas of Canterbury into four categories, based on area-wide land assessments, to help inform decisions about repair and reconstruction.

5.43

The assessments used information on the damage to land, buildings, and infrastructure to work out what the different policies and procedures for repairing homes and buildings should be. The assessments considered matters of timeliness, cost-effectiveness, certainty, disruption, and the well-being of communities.54

5.44

The four zones were called red, orange, green, and white zones. Orange zones have since been assessed and put into the red or green zones.55 All residential properties in the earthquake-affected areas of Canterbury now fit into one of three zones:

- red where damage was extensive, the risk of further damage is high, and it is uneconomic to repair properties;

- green considered to be viable and suitable for continued residential occupation; and

- white in the Port Hills, where mapping and final zoning decisions have recently been made.

5.45

As of 18 May 2012, there were 7256 properties inside the red zone.56 On 29 June 2012, the Government announced that 285 properties in the Port Hills had also been zoned red. On 13 September 2012, the Minister announced that a further 37 properties at risk from rock falls had been zoned red. The residential red zone is mostly in the east of Christchurch (along the Avon River and other areas near waterways), the north-east of Christchurch (such as Brooklands), the beach areas of Waimakariri District (Pines Beach and Karaki Beach), Kaiapoi, and, more recently, the Port Hills.

5.46

The Government defines the red zone as areas where:

- land repair would be prolonged and uneconomic;

- land has suffered significant and extensive damage;

- most buildings are uneconomic to repair;

- there is a high risk of further damage to land and buildings from aftershocks, flooding, or spring tides;

- infrastructure needs to be completely rebuilt;

- land repair solutions would be difficult to carry out, prolonged, and disruptive for landowners; and

- rebuilding is unlikely in the short to medium term because of the obstacles posed by the significant land or infrastructure damage and high risk of further damage.

5.47

In June 2011, the Government announced a package to buy insured residential properties in the first areas confirmed as being in the red zone. The same offer has been made available in all residential areas that are zoned red.

5.48

Under the Government's package, residents in the red zone who own insured residential property have two options:

- Option 1: CERA, acting for the Government, buys the property at a price based on the most recent rating valuation for the land and improvements. The Crown takes over any insurance claims for the property.

- Option 2: CERA, acting for the Government, buys the property at a price based on the most recent rating valuation for the land. The Crown takes over the EQC claim for land damage only. These claims are managed by CERA. The owner retains the benefit of all insurance claims for damage to the property.

Who is responsible for what?

5.49

CERA has overall responsibility for administering the red zone offer. This includes communicating the offer to residents, making the offers, buying, managing, and demolishing the properties, and recovering insurance on the properties that the Government has bought.

5.50

No decisions have been made on who will be responsible for managing the land in the residential red zone in the future. Until future land use is worked out, CERA will manage the land on behalf of the Crown. CCC and Waimakariri District Council are working with CERA to prepare plans for managing this land. In the meantime, while residents progress with their settlements and gradually move out of the red zoned suburbs, CCC and Waimakariri District Council continue to provide infrastructure and services to properties. The unit cost of these services increases as more people move out of the red zone.

Costs and funding arrangements

5.51

CERF funds the Government's red zone offer. There are also appropriations in Vote Canterbury Earthquake Recovery that fund CERA's work on managing red zone properties. Figure 12 sets out the relevant appropriation budgets for CERA's spending on the residential red zone.

Figure 12

Red zone costs and liabilities for the Government

| Appropriation | Budgeted 2011/12* $million | Budgeted 2012/13** $million |

|---|---|---|

| Managing voluntarily acquired insured residential properties | 4.2 | 1.0 |

| Buying further red zone properties | 3.0 | nil |

| Buying Christchurch red zone properties | 569.5 | nil |

| Contributing towards legal fees incurred by owners of properties in the red zone | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| Managing voluntarily acquired insured residential red zone properties | 84.7 | 10.0 |

| Total | 664.6 | 13.0 |

* Addition to the Supplementary Estimates of Appropriations for the Government of New Zealand and Supporting Information, for the year ending 30 June 2012, Vote Canterbury Earthquake, June 2012, page 875. ** The Estimates of Appropriations for the Government of New Zealand, for the year ending 30 June 2013, May 2012, page 21.

5.52

The Government will recover some of the cost of buying properties in the red zone through claims to insurance companies and EQC for the land and buildings, but the total amount that will be recovered is still being worked out. The eventual amount of money recovered will depend on the different insurance policies that cover the properties that the Government has bought.

5.53

CERA is considering how to value the residential red zone land that it has bought, and what will be done with the land.

What is the effect on residents?

5.54

Figure 13 shows the complex range of matters and decisions that home owners in the red zone must manage.

Figure 13

What the Crown's offer to buy properties means for people living in the red zone

5.55

Figure 13 shows that completing the Crown's offer involves working with many different organisations and agencies, including EQC, insurance companies, lawyers, architects, CERA, and the relevant local authority. This can be challenging, especially for elderly home owners and other vulnerable groups.

5.56

The most important decision for property owners is whether to take Option 1 or Option 2. The best option for property owners will depend on several factors, including the particular insurance policy they have, the extent of the damage to their property, and what insurance or EQC payments they received before the Crown's offer.

5.57

When choosing Option 2, property owners must settle their EQC and insurance claims before they can buy or build a new house. While they are settling claims with their insurers, property owners often pay for rental accommodation and mortgages. Some property owners live in their damaged homes until they settle their claims.

5.58

Some property owners have disagreements with their insurers on the amount that they are entitled to. For example, some property owners chose Option 2 because preliminary assessments led them to believe that their insurer would pay out the replacement value of their house. However, in some instances, property owners have found that their insurers will fund repairs to properties but not a rebuild. In these instances, property owners may face a shortfall in funding the cost of rebuilding, or buying a property, elsewhere. While these matters are being resolved, property owners are unable to take up the Crown's offer. Property owners have 12 months from the date of their offer letter to accept the Crown's offer.

5.59

The red zone offer is voluntary, and owners of properties are under no obligation to accept it. It is not certain what will happen if some property owners choose to stay in the red zone after the Crown's offer expires.

5.60

Soon after the Government announced the red zone offer, CERA held eight workshops in Christchurch and one in Kaiapoi to explain the two options and to answer questions from property owners. At the same time, CERA staff visited all homes in the red zone to explain the zoning decision, the implications for residents, and the options available to them.

5.61

CERA and other public entities, such as the Commission for Financial Literacy and Retirement Income, have published information to help property owners to make the best decision about their property. Property owners can also access subsidised legal advice and get funding to help pay for their legal costs.

5.62

Help and support for property owners in the red zone includes:

- a free guide, Red Zone Financial Decision Guide for Residential Red Zone Property Owners, produced by the Commission for Financial Literacy and Retirement Income and funded by the Christchurch Earthquake Appeal Fund;

- a financial advisory service set up by the Commission for Financial Literacy and Retirement Income that uses qualified financial advisors who have agreed to provide their time and services at no charge;

- a discount of up to 50% on the cost of legal advice, funded by CERA and estimated to cost about $3.8 million;

- two Earthquake Assistance Centres, one at the Avondale Golf Club and the other in Kaiapoi, where people can get advice and help with matters relating to the Government's red zone offer, as well as access to other services; and

- financial help from CETAS (see paragraph 2.98), which is available to home owners whose homes are uninhabitable and whose insurance cover for temporary housing has run out. Temporary accommodation assistance is available to all home owners to help pay for rent and motel costs.

Case study 4: Damaged properties in Technical Category 3 areas

What happened?

5.63

After CERA made its announcement on the different land zones in greater Christchurch, the then Department of Building and Housing assessed land damage in the green zone (see paragraph 5.44). Land in the green zone is still generally considered suitable for residential construction but some properties have experienced liquefaction and considerable settlement during the series of earthquakes. The Department of Building and Housing analysed land damage, property damage, groundwater depth, and underlying soil composition.

5.64

After assessing the land, the Department of Building and Housing categorised land in the green zone into three technical categories, which affect the type of guidance provided for repairs and for new buildings.57

5.65

Houses with foundations that are built correctly to meet the ground conditions will perform better in future earthquakes. The three technical categories form an important part of MBIE's guidance for the repair and rebuilding of houses. They are a guide to how much geotechnical investigation is required (and who should do it) to work out the most appropriate foundation for a house.

5.66

Technical Category 1 land is unlikely to be damaged by liquefaction or movement in an earthquake. Standard foundations or enhanced concrete slab foundations recommended for most standard timber-framed homes can be used. The only site-specific geotechnical investigation required is a shallow soil strength test, which is standard for all homes.

5.67

Technical Category 2 land will suffer minor damage in a small earthquake and moderate damage in a major earthquake. Standard or enhanced concrete slab foundations can be used. The only site-specific geotechnical investigation required is the shallow soil strength test.

5.68

In an earthquake, liquefaction and lateral movement is likely to significantly affect TC3 land. Further geotechnical information is required on TC3 land to provide certainty about foundation repair and replacement options because there is no "one size fits all" solution. MBIE guidance recommends three foundation types for TC3 land – deep piles, site ground improvement options, and surface structures with shallow foundations. Chartered professional engineers will use the information gathered from geotechnical investigations to design the most appropriate foundations.

5.69

The three technical categories reflect the variable nature of the Canterbury soils. The categories provide a starting point for repair or rebuilding of earthquake-damaged house foundations by directing engineering resources where they would be needed most – to areas where the land is most susceptible to liquefaction and lateral movement in an earthquake. MBIE estimates that about 80% of houses in the green zone on flat land do not need deep geotechnical investigations and specific foundation designs.

5.70

For TC3 houses that have suffered damage to foundations, the land requires deep geotechnical investigations (by drilling) to inform a tailored design for repairs to the foundations. These properties will need more rigid foundations or site-specific foundation designs to reduce the risk of injury to people and damage to homes in any future earthquakes.

5.71

The Department of Building and Housing introduced technical guidance for foundations. Undamaged foundations will still meet building standards because building code changes do not apply retrospectively.58

5.72

The Department of Building and Housing issued guidelines for repairing and rebuilding foundations for TC3 properties. The guidelines include methods that can be used to make properties safe and compliant with the new building code, subject to normal engineering, building, and consenting standards.

5.73

EQC has initiated a drilling programme to gather the geotechnical information needed to design new foundations, for claims that are below the EQC cap that are EQC's responsibility.59 The drilling programme is to be carried out suburb by suburb during 2012 and 2013. The timetable for the drilling programme is published on the EQC website.

Who is responsible for what?

5.74

Under section 19 of the Earthquake Commission Act, EQC is liable for the cost of land damage to residential properties, but EQC cover for land damage is not designed to change the technical category of property, or reduce the future risk of liquefaction. Insurance policies do not normally include liability for damage to land, but will normally include liability for repairing the foundations to houses.

5.75

MBIE is responsible for building standards and publishing guidance on engineering solutions for repairs to houses with damaged foundations in TC3 areas.

5.76

CERA has co-ordinated community meetings in TC3 areas so that residents and property owners have been able to ask representatives from EQC, insurance companies, the Department of Building and Housing and CCC about TC3 matters.

Costs and funding arrangements

5.77

EQC estimates that the overall costs of the drilling programme to be about $50 million. The cost of damage assessments and geotechnical investigations such as the drilling programme form part of the EQC cap for each event for each property.

What is the effect on residents?

5.78

Figure 14 shows some of the issues that owners of damaged property in TC3 areas must manage and the different agencies and organisations that they must work with to resolve them.

Figure 14

Matters that owners of damaged property in Technical Category 3 areas must manage

5.79

Of about 28,000 houses in TC3 areas, EQC estimates that between 10,000 and 12,000 will require repairs to foundations. Owners of property in TC3 areas that have damaged foundations need to have the land around their property assessed geotechnically to confirm the appropriate method of repair. Until a design solution has been worked out for houses with foundation damage in TC3 areas, property owners cannot proceed with repairs.

Case Study 5: Risks to homes in the Port Hills

What happened?

5.80

The earthquakes of 22 February and 13 June 2011 caused rock falls, cliff collapses, and landslides in many parts of the Port Hills, a rugged area to the south and east of urban Christchurch, within the Christchurch City Council boundary. These destroyed some homes, damaged others, and put many at increased risk of damage in a future earthquake.60

5.81

Since the earthquakes, CERA and CCC have carried out work to assess the risks to property and life in the Port Hills. Many owners of properties in the Port Hills had not been able to begin repairing their homes until these risks had been accurately assessed.

5.82

The recovery process for the Port Hills is more complicated than on the flat land, because it involves unusual geotechnical hazards and risks to human life. For CERA to work out the best future for the Port Hills, and for CCC to decide about the safety of individual homes, geotechnical experts have to assess each risk.

5.83

CCC commissioned GNS Science to assess earthquake damage in the Port Hills and to work out the resulting risks to property and people. CERA commissioned a three-dimensional rock fall study to help identify protection measures that might be suitable to shelter properties from rock falls.61

5.84

Assessing these risks and how to manage them is challenging. At first, engineers used assessment methods prepared from overseas examples, but the substantial damage from the 13 June 2011 earthquake showed that these methods were inadequate to effectively work out the current and future risks to life and property.62

5.85

When risks have been worked out, engineering solutions need to be considered to manage those risks so the danger to people can be minimised. Possible solutions include building fences, retaining walls, and other forms of barriers to prevent falling rocks from hitting buildings. There are no standards for structures that are erected for remediation, and insurance companies will need to agree that the solutions adopted reduce the hazard satisfactorily.

5.86

After geotechnical investigations and analysis and further geotechnical work, CERA has made decisions about the future of most houses in the Port Hills:

- On 5 September 2011, 9700 residential properties in the Port Hills white zone were zoned green, with about 3700 properties remaining in the white zone for further investigation.63 CERA wrote a letter to all property owners explaining the zoning decision.

- On 19 December 2011, CERA made a second announcement, rezoning a further 1600 homes to green. Because of the complex nature of investigations, CERA was unable to put a time frame on further announcements until recently.

- On 18 May 2012, the Minister announced that 421 properties in the Port Hills had been zoned green.

- On 29 June 2012, 285 properties were zoned red and 1107 were zoned green. On 13 September 2012, 37 properties at risk from rock falls were also zoned red.

Who is responsible for what?

5.87

The situation in the Port Hills presents a unique and complex set of challenges for public entities and residents. Because the extent and type of rock fall risk is unprecedented, it is difficult for CCC and CERA to work out and assess the level of risks to property and life and to find ways to manage those risks.

5.88

CCC has statutory obligations under the Local Government Act 2002, the Building Act 2004, and the Resource Management Act 1991, which include making decisions about the use of buildings, including declaring buildings to be unsafe and uninhabitable. Under these obligations, CCC has responsibility for assessing the hillside land and properties in the Port Hills and issuing section 124 notices (often called "red stickers") to properties that it believes are unsafe because they are prone to rock falls.64

5.89

CERA has responsibility for making decisions about land use in the Port Hills, so it works closely with CCC to assess risks and land-use policy. CERA must tell the affected communities when it decides about land use.65 CERA has organised community meetings that have also involved CCC and EQC.

5.90

CCC and CERA are working closely together on the Port Hills project and CERA is preparing a cost-benefit analysis. A signed partnership agreement between CERA, CCC, and the other local authorities forms the basis of their working arrangement. A memorandum of understanding outlines more clearly the respective roles and responsibilities of the agencies involved, particularly CERA and CCC.

Costs and funding arrangements

5.91

CCC has paid for the work that the Port Hills Geotechnical Group has carried out. Rock fall work to June 2012 cost $19.7 million. The project spending has been on mapping and field assessment, risk reporting, and physical works for reducing imminent risk. Vote CERA (Supplementary Estimates 2011/12) includes an appropriation of $10 million for reimbursing CCC for the Crown's share of the costs to procure rock fall protection systems.66

5.92

The decisions about land use and remediation in the Port Hills have long-term cost implications. Protective infrastructure, such as fencing, is costly to maintain (the through-life costs have been built into the cost-benefit analysis) and creates expectations for more infrastructure to be built if further areas are identified as dangerous.

What is the effect on residents?

5.93

Owners of properties in the Port Hills have experienced different situations, with varying risks and strains. Some people have been out of their properties for more than a year, paying mortgages for houses they cannot live in and paying rent to live elsewhere.

5.94

Because the future has been uncertain, many people commute long distances to schools and jobs, and are under considerable financial strain. Many have made short-term accommodation arrangements, paying higher rent as a result, because time frames have been not been worked out.

5.95

Figure 15 shows the complex range of matters confronting owners of properties in the Port Hills.

5.96

In some instances, property owners have houses that are not directly at risk, but are surrounded by properties (or driveways) that are at risk and no longer inhabited. This has left some people isolated and unable to move – the lack of damage means there is little chance of an insurance settlement and their properties will be difficult to sell.

Figure 15

Matters that Port Hills property owners must manage

50: See the Stronger Christchurch Infrastructure Rebuild Team's website, www.strongerchristchurch.govt.nz.

51: Christchurch City Council (2012), Annual Plan 2012–13, page 18.

52: Waimakariri District Council (2012), Ten year plan 2012–2022, page 28.

53: Selwyn District Council (2011), Annual Report 2010/11, page 125.

54: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (December 2011), Technical categories and your property.

55: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (December 2011), Technical categories and your property.

56: See the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority's website, www.cera.govt.nz.

57: Department of Building and Housing (2012), Guidance Appendix C Repairing and Rebuilding Foundations in TC3 Areas, page 12.

58: Earthquake Commission (2012), Land information – Technical Category 3 (TC3).

59: Earthquake Commission (2012), EQC Connects.

60: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (February 2012), Port Hills White Zone: Information for Property Owners in the Port Hills White Zone.

61: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (February 2012), Port Hills White Zone: Information for Property Owners in the Port Hills White Zone.

62: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (May 2012), Port Hills White Zone Issues.

63: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (2012) Port Hills Land Announcement, available at www.cera.govt.nz.

64: Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (2012) Port Hills White Zone Issues, available at www.cera.govt.nz.

65: See website of the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority, www.cera.govt.nz.

66: Addition to the Supplementary Estimates of Appropriations for the Government of New Zealand and Supporting Information for the year ending 30 June 2012, Vote Canterbury Earthquake, June 2012, page 876.

page top