Part 6: The 2013 Statement

6.1

In this Part, we focus on the 2013 Statement, released by the Treasury on 11 July 2013.

The form and focus of the 2013 Statement

6.2

The 2013 Statement reflects the Treasury's ongoing efforts to improve the usefulness of the long-term financial statement. It is written clearly, with less of the technical content and language found in previous statements. We consider it a positive step in readability and understandability for its intended audiences (the general public, members of Parliament, and the media).

6.3

The Treasury told us that the 2013 Statement was written as a high-level communications document, with a lot of the technical detail contained in the set of accompanying research papers. These papers cover many matters relevant to financial sustainability. The Treasury regards these papers as part of the 2013 Statement.

6.4

We have focused on what the 2013 Statement says. Although we refer to some, we have not reviewed the set of accompanying research papers in detail.

6.5

The 2013 Statement is presented in two Parts:

- Part 1 covers the introduction to financial sustainability, summarises the future financial challenges, and discusses how to think about the size of the adjustment needed; and

- Part 2 discusses some options that might help address those financial challenges and, in doing so, move towards a more sustainable path.37

6.6

The 2013 Statement provides a good introduction to some of the matters that could affect government activities and how these could affect New Zealanders' living standards. However, these broader perspectives do not appear to have been reflected in the 2013 Statement's main messages, which remain focused on the ageing population, government spending, and government debt.

6.7

In contrast, Australia's Intergenerational Report uses graphs and tables related to various social, economic, and environmental indicators to describe the challenges of the next 40 years. The United Kingdom's Office for Budget Responsibility's Fiscal Sustainability Report is also more comprehensive and uses more sensitivity and "fiscal gap" analyses.

The main factors affecting financial sustainability

6.8

The 2013 Statement explains that financial sustainability "refers to whether the government is able to maintain current policies without major adjustments in the future".38 Importantly, the 2013 Statement says the principle of financial sustainability "is embedded in the Public Finance Act 1989, which requires governments to maintain a prudent level of government debt".39

6.9

The 2013 Statement explains that there are various things that will affect government activities and policies over the long term and, throughout, references are made to how sensitive the economy and government finances are to natural and economic shocks. There is a list of nine historic shocks, with an acknowledgement that "good fiscal management means understanding the worst that may happen".40

6.10

Also, specific mention is made of New Zealand's "high levels of net external debt", raising important questions about New Zealand's resilience in times of crisis.41

6.11

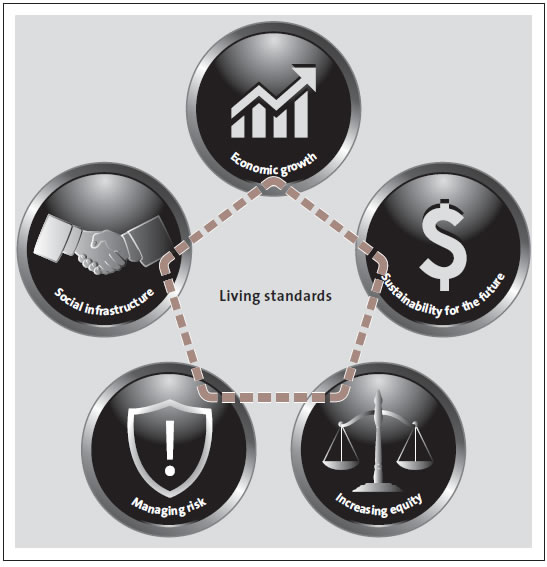

Recognising the need to think beyond debt levels and to think about how different policy options can affect people's living standards, the 2013 Statement introduces the Treasury's Living Standards Framework as another way of thinking more broadly about what New Zealanders find important.

6.12

Figure 6, based on a figure in the 2013 Statement, shows the five elements of the Living Standards Framework. All elements are interrelated, and include (and expand on) many of the potential drivers of long-term financial sustainability.

Figure 6

The five elements of the Treasury's Living Standards Framework

Source: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 24.

6.13

The elements of the Living Standards Framework are compatible with the 2013 Statement's broad description of financial sustainability and are used to discuss the implications of the various policy responses.42

6.14

However, notwithstanding the broader description of financial sustainability, the emphasis of the 2013 Statement is on how current settings might be adjusted, rather than what the future might demand of the public sector.

Nature and profile of the financial challenge

6.15

The financial projection in the 2013 Statement is designed to give an idea of the size of the financial challenge. However, it is not a prediction of what is likely to happen. The 2013 Statement emphasises that the projection of net debt to GDP is based on a scenario that differs from the Government's current financial strategy "which involves firm control of expenditure growth".43

The financial projection

6.16

Figure 7 shows the financial projection in the 2013 Statement. The projection reflects what would happen if governments were to hold tax revenues constant as a percentage of GDP and allow expenses to grow faster, in line with historic trends and population forecasts.

Figure 7

Summary financial projection in Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position

| % of nominal GDP | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | 6.8 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 8.9 | 9.9 | 10.8 |

| New Zealand superannuation | 4.3 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.9 |

| Education | 6.1 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| Law and order | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Welfare (excluding New Zealand Superannuation) | 6.7 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| Other | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Debt-financing costs | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 7.1 | 11.7 |

| Total government expenses | 33.4 | 30.8 | 33.4 | 36.9 | 40.6 | 46.8 |

| Tax revenue | 26.5 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 29.0 |

| Other revenue | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Total government revenue | 29.7 | 31.9 | 32.2 | 32.2 | 32.3 | 32.6 |

| Expenses less revenue | 3.6 | (1.1) | 1.2 | 4.6 | 8.3 | 14.3 |

| Net government debt | 13.9 | 27.4 | 37.1 | 67.2 | 118.9 | 198.3 |

Note: Numbers are rounded.

Source: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 4.

6.17

Figure 7 shows two main areas of government spending that are expected to grow significantly healthcare and superannuation. From about 2030, the projection indicates that the Government will need to borrow an increasing amount to balance its budget, based on current policy settings. If nothing is done to address the growing deficit (the Expenses less revenues line), then debt-financing costs in 2060 are projected to be 11.7% of GDP a year and net debt is projected to be 198.3% of GDP.

6.18

Future expenditure on investments and property are not shown in the projection. The Treasury notes that: "Amounts borrowed for capital expenditure are reflected in the ‘Net government debt line'."44 We consider that this projection should have included at least a separate capital expenditure projection to clearly show how capital expenditure affects the movement in net debt. We note that, in the projections, the operating expenses of government include depreciation, which is often used as a proxy for capital expenditure.

The financial challenge ahead

6.19

Clearly, a net-debt-to-GDP percentage of 198.3% in 2060 is very high. However, it is not clear when the level of net debt is expected to become a problem and, compared to 2060, net debt to GDP of 37.1% in 2030 seems more manageable.

6.20

Although this could suggest that there is no immediate problem, importantly, the 2013 Statement is clear that delaying adjustment means that more significant adjustments will be needed. It will also take longer to implement because of the compounding effect of debt-financing costs.45

6.21

Although the 2013 Statement highlights many important matters relating to financial sustainability, we think that more could have been included to help readers to understand the nature of the financial problem, and the challenges and opportunities that surround it.

6.22

For example, more could have been said about how much government tax revenue is expected to be spent on delivering public services and how much on interest costs, and how this would affect the percentage of net debt to GDP.

6.23

This could help answer two important questions about future government spending and debt levels:

- Are governments expected to spend more than they earn on core services?

- What is driving the expected increase in net debt?

6.24

The cost of core services of government does not include the cost of interest. Figure 8 uses the Treasury's projection to show that, from 2015 to 2031, governments are expected to spend less than they earn on core services (they are in surplus) but this is assumed to reverse from 2032. Figure 8 shows a gradual increase in net operational spending after 2032, with the added borrowing leading to a compounding interest cost that becomes increasingly significant.

Figure 8

Net operating expenditure and interest cost as a percentage of revenue, 2013 to 2060

6.25

Figure 9 uses the Treasury's projection to show that, for the first 30 years (until 2042), net debt increases by slightly more than $500 billion (or about $17 billion a year on average), driven mainly by assumptions about government spending and increases in asset values. However, for the last 18 years of the projection, net debt increases by about $2,350 billion (or around $130 billion a year on average), driven largely by compounding interest costs (highlighted in Figure 8) that add more to debt than government overspending on operations.

Figure 9

Contribution of net operating expenditure and interest cost to net debt, 2013 to 2060

6.26

Our main observations are that:

- from 2015 to 2031, the projected net operating expenditure (revenues less expenses) is in surplus and that, because of this, the increase in net debt is relatively small and controllable;

- this surplus reverses to a deficit from 2032 to 2060, but the trend of gradual increases in net operating expenditure continues; and

- if nothing is done, then, from 2032, governments will need to start borrowing more to cover the cost of interest, leading to an interest-driven debt spiral.

6.27

One implication of the above is that during the early years, relatively small and gradual changes to revenue, expenditure, or asset and other liability values could significantly reduce the build-up of net debt in future years. In other words, the 2013 Statement's projection is sensitive to changing certain assumptions – especially in the early years.

6.28

The 2013 Statement states that the financial projections are sensitive to the assumptions that the Treasury made in producing them. However, it also states that "changing our assumptions within reasonable parameters does not make much difference to the overall projections".46 How big or small that difference could become, or how it could affect the main financial indicator itself, is not shown.

6.29

In one of the Treasury's research papers, some sensitivity analysis (using the 2013 model) looks at how changing an individual demographic, economic and financial assumption could affect the main financial debt indicator. Although this analysis does not reflect the relationships between the assumptions, it provides some relevant information, such as "if more of us worked, or worked longer hours, or we worked more productively, that would help, but it wouldn't solve the fiscal challenge".47

6.30

However, we consider that more could have been said about the potential financial effect of some important downside risks. For instance, although the 2013 Statement says that "One lesson from the recent financial crisis is that government debt can rise much faster than it falls",48 the financial consequences of potential financial or natural shocks on the profile of government spending and debt are not shown.

Government debt and the financial sustainability problem

6.31

The Treasury's primary indicator of a financial sustainability problem is the percentage of net debt to GDP. To help understand this better, the 2013 Statement explains some aspects of what government debt is and notes that, although "high government debt can have negative impacts", low government debt provides a buffer.49

6.32

The 2013 Statement notes that the Treasury has advised the Government that net debt to GDP of 20% is prudent over the period up until 2020.50

6.33

The percentage of net debt to GDP is widely used internationally as an indicator of financial sustainability.

6.34

Research suggests that gross debt to GDP of more than 80%, coupled with sustained current account deficits, may result in a potential financial problem for a government.51

6.35

In our view, using the percentage of net debt to GDP alone is not enough to explain to readers of the 2013 Statement the long-term financial health of government. For instance, in certain circumstances, taking on further debt may be beneficial to financial sustainability. For example, "Borrowing to finance productive infrastructure raises long-run potential growth, ultimately pulling debt ratios lower."52

6.36

In practice, other financial indicators such as net external debt (including private sector debt), net financial assets, net worth, and the ratio of interest costs to revenue are commonly used to help explain the long-term financial health of government. Some of these indicators are discussed in an accompanying research paper to the 2013 Statement.53

6.37

Paragraphs 6.23-6.27 show that, from sometime between 2040 and 2045, interest costs will start to add more to government debt than government overspending. International practice suggests that this would become a serious problem when interest costs become greater than 10-15% of the government's taxation revenue. Using 15% and applying this to the Treasury's projection suggests a serious problem in about 2042 and illustrates that the cost of debt is as important as the size of debt.

6.38

In our view, the financial sustainability problem that governments will face could be restated in broader terms to make it more relevant to a wider range of readers. The use of additional indicators, not necessarily just financial, may also have been helpful.

Improving financial sustainability

6.39

The 2013 Statement says that future financial challenges mean that the Government needs to move towards achieving a prudent level of net debt to GDP of 20% and then maintain it, on average, thereafter. Achieving this 20% level will "require firm fiscal management" and making some important policy decisions over the next decade.54 However, the longer the delay, the larger the changes to government expenditure or revenues will need to be.

6.40

In effect, the Treasury's view is that, regardless of what happens in the future, moving sooner rather than later towards a prudent net debt level will allow future governments to better manage their financial position.

6.41

The 2013 Statement suggests that net debt to GDP of 20% is enough of a buffer to manage any unexpected changes over the long term. However, no sensitivity analysis is included to help readers to understand how unexpected changes could affect governments' ability to achieve the 20% target over the long term.

6.42

The 2013 Statement puts forward and reviews various alternatives in terms of their contribution to a prudent spending path. Their potential effect on New Zealanders' living standards is discussed. These alternatives can be grouped into three main areas:

- collecting more tax revenue;

- spending less (focusing on healthcare); and

- responding to demographic change (focusing on the growth in New Zealand superannuation spending).

6.43

The 2013 Statement notes that these alternatives "individually would get us closer – although not all the way – to a sustainable long-term fiscal position".55 The accompanying research papers provide further details about these and other policy options.

6.44

Appropriately, the Treasury makes no specific policy recommendation based on these alternatives but does recommend that "governments develop plans to address these cost pressures over the course of the rest of this decade".56

6.45

We think a more informed and wider discussion about available choices would also have been possible within the 2013 Statement if further information were available on the size, profile, and potential variability of the problem. Paragraphs 6.46-6.48 provide examples of this.

6.46

If the potential effects of future uncertainties (either positive or negative) were better understood, the level and urgency of the response might be different. Sensitivity analysis would have allowed an understanding of the financial impact if something unexpected happens, whether the 20% target was enough to cover it, and what a shock (or two) might mean for meeting and maintaining the target in the long run.

6.47

If a wider set of indicators were used, the form of response might have been different. Indicators such as net financial assets might have resulted in more discussion about using financial assets, such as those held by the Earthquake Commission and the New Zealand Superannuation Fund, to help manage financial sustainability. Generally speaking, we think good management of government assets and other non-debt liabilities can play an important role in managing the sustainability of the Government's finances.

6.48

If the relationships between the drivers were better understood, the design of the response might be different. As an example, understanding how educational achievement affects healthcare and/or future government revenues, even in a simplified way, might allow a more integrated solution.

37: The annexes in Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position describe how the future paths of some major government spending and revenues are expected to change until 2060, list some of the main assumptions, comparing them to the 2009 Statement, and briefly outline how Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position was prepared.

38: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 11.

39: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 11.

40: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 13.

41: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 3.

42: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, pages 5 and 24.

43: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 3.

44: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 16.

45: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 5. See an accompanying paper, "Fiscal Sustainability Under an Ageing Population Structure", available at www.treasury.govt.nz, for more detail.

46: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 18.

47: Rodway, P. (2012), "Long-term Fiscal Projections: Reassessing Assumptions, Testing New Perspectives", page 40.

48: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 13.

49: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, pages 11-12.

50: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 3.

51: Greenlaw, D. et al (2013) "Crunch Time: Fiscal Crises and the Role of Monetary Policy", a paper for the United States Monetary Policy Forum, New York, available at http://dss.ucsd.edu.

52: Reinhart, C. and Rogoff, K. (1 May 2013), "Austerity is not the only answer to a debt problem" in The Financial Times, available at www.ft.com.

53: See Buckle, R. and Cruickshank, A. (2012), "The Requirements for Long-Run Fiscal Sustainability", pages 8-9.

54: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 13.

55: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 30.

56: The Treasury (2013), Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position, page 5.

page top