3. About this independent review: purpose, scope, context and approach

Purpose and Scope of the Review

75. This review assesses the sufficiency and appropriateness of Audit New Zealand’s audits of Kaipara District Council from 2003 to 2012.4 It forms part of the Auditor‐General’s broader inquiry into the Council’s development, implementation and oversight of the Mangawhai Community Wastewater Scheme.

76. The full terms of reference for the inquiry appear as Appendix 1. In summary, they require me to assess whether Audit New Zealand’s work was carried out in accordance with the auditing and assurance standards (including those issued by the Auditor‐General) that applied at the time. Specifically, I am required to assess its audits of the following Council accountability documents:

- Long Term Community Council Plans (‘LTCCPs’) for 2006 and 2009

- Long Term Plan for 2012

- Annual Reports for 2003 to 2012

- Annual Plans for 2003 to 20125.

77. Given the emphasis of the Auditor‐General’s broader inquiry, my own review focuses particularly on those aspects of the audit engagement where the auditor considered (or could have been expected to consider) the Council’s development of the wastewater project.

78. My review addresses the following areas and questions:

Planning and performance of the audit engagement

When planning and performing the audits, did the auditors sufficiently and appropriately:

- focus on significant material risks or financial matters, including in relation to the Mangawhai scheme?

- plan the audits so that they addressed matters required in the relevant legislation, and then ensure these matters were actually addressed when the audits were performed?

- plan the audits with due care, competence and independence, and with sufficient professional judgment and scepticism?

- develop and apply appropriate quality control mechanisms?

- take into account significant issues affecting the Council’s financial management?

- communicate with Council staff?

- use adequate and appropriate resources, including appropriately‐skilled staff or experts?

Audit reporting and conclusions

- Were the auditors’ conclusions supported by sufficient and appropriate evidence?

- Were the auditors’ conclusions appropriately reported, both in the audit report and management letters?

Audit documentation

- Do the audit files contain sufficient and appropriate documentation of the audits?

- Do the audit files show the auditors obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to support their conclusions?

- Audit methodology

- Were audits of the Council consistent with, and supported by, Audit New Zealand audit methodology?

Audit communications

- Were the audit opinions expressed in the audits appropriate?

- Were the management letters communicating the results of the audits appropriate?

Structure of this Report

79. This report examines the audits of each Council accountability document, as well as the auditors’ assessment of the Council’s statutory compliance, in light of the topics and questions listed above:

- Section 4.1 examines the audits of the Council’s Annual Reports.

- Section 4.2 examines the auditors’ approach to assessing the Council’s compliance with legislative requirements.

- Section 4.3 examines the audits of the LTCCP and LTP.

- Section 4.4 looks at the quality control mechanisms used by the auditor in each of these audit engagements.

- In Section 4.5, I turn to the auditing of the Council’s rates revenue. For reasons I set out in paragraphs 84‐86, I consider it essential to examine this aspect of Audit New Zealand’s performance even though the Terms of Reference do not specifically require me to.

- Finally, Section 4.6 examines the merits of the auditors’ conclusions following each audit engagement, and the appropriateness of the reports and opinions issued.

- Throughout, I describe what happened, draw conclusions and, where appropriate, make findings. My conclusions and findings are brought together in a short summary in Section 4.6.

80. Before moving onto the substantive part of the report, it is necessary to set out some important context. The next section describes the high level of community interest in the matters which prompted this inquiry, and how this has influenced my approach. I then briefly summarise the nature of the auditor’s role and responsibilities when auditing local authorities, and the purpose and scope of the audit function. Finally, I outline my methodology.

The context for the review

Significant Public Interest

81. Numerous deficiencies and irregularities in the Council’s management and funding of the Mangawhai wastewater project were identified when this review was initiated, and have since become public knowledge. Many extend back over multiple financial periods. Understandably, these irregularities have prompted considerable community concern, and questions have been asked about why the Council’s auditor did not identify them.

82. The high level of interest presents me with particular challenges in performing this review. Whenever there is public alarm about the performance or management of public entities, confusion can arise about the role of an auditor, the extent to which their work can be relied on, and the degree of assurance that can be taken from an audit opinion. The risk of misplaced expectations and misunderstandings about the audit process is often referred to as the audit expectation gap.

83. In preparing this report, I have therefore been mindful of the need to clarify the role, purpose and responsibilities of the auditor; and the scope and objectives of each audit engagement. (The next section of this report, Purpose and objectives of an audit, deals with these matters.) I have also been careful to clearly differentiate between the respective roles and responsibilities of the auditor and those of the Council. My objective is to ensure that people who read my findings and observations have a broader context of understanding about the audit process, its purpose and inherent limitations.

84. The Kaipara District Council (Validation of Rates and Other Matters) Bill currently before Parliament6 has also attracted significant public interest, and thus forms an important part of the wider context for my review. The Bill, which was promoted by the Council during the course of this inquiry, seeks to validate irregularities in its setting and assessment of rates under the Local Government (Rating) Act 2002 (the LGRA) and the Local Government Act 2002. The Council acknowledges irregularities occurred in the financial years 2006/2007 – 2011/2012 (inclusive).

85. Although these rating irregularities fall within the overall period covered by this review, my terms of reference do not explicitly require me to consider the matters addressed in the Bill. However, those irregularities relate specifically to the Council’s primary source of income, as disclosed in both the financial statements and Council planning documents. In addition, I am aware that Audit New Zealand’s audit methodology specifically requires the auditor to plan and perform test procedures designed to assess the Council’s compliance with key requirements of the LGRA. Moreover, as I have noted, the progress of the Bill is being keenly followed by the community. Notwithstanding the scope or objectives of the audit engagement, there is significant public interest in understanding why the auditor did not identify the rating irregularities.

86. For all these reasons, my review specifically examines the auditor’s approach to the auditing of rates revenue during those periods in which the Council has acknowledged irregularities occurred.

The audit process and local authorities: an overview

Introduction

87. Any assessment of an auditor’s performance must be informed by a clear understanding of several things. First, it is imperative to understand in a general sense what an audit is and what it is not. Second, an understanding is needed of the requirements, benchmarks and expectations of the particular auditor and audit engagements under review. It is particularly important to understand the expectations of the auditor and the audit in effect at the time that the audit was performed.

88. Any assessment also needs to acknowledge the risk of retrospection. When performing an audit, auditors must exercise significant professional judgment and scepticism as they consider the sufficiency and appropriateness of the evidence available to them. By contrast, in undertaking my review, I have had access to many years of audit files that may not have been available to the auditor at the time the audit was performed, and of course the advantages of hindsight. This risk needs to be carefully managed.

89. In this instance, I am examining audit engagements performed between 2003 and 2012. During that time, there were three different auditors7 appointed by the Auditor‐General to carry out the audit engagement. The methodology and standards applying to the audit continued to evolve, as did the nature and extent of issues associated with the wastewater project. Because of this ongoing change, it is entirely possible to reach different conclusions about the various audit engagements carried out over the period.

90. The performance of the audit requires interface between the audit team, Audit New Zealand and the OAG. The nature and extent of the interface varies depending on the nature of the audit engagement, the extent of issues identified and the consideration of reporting matters. For example, the audit of the Council’s annual report is performed in accordance with the methodology developed by Audit New Zealand. In contrast, the methodology and approach to the audit of the Council’s planning documents is determined by the OAG. Further, significant issues that may have an impact on the report issued by the auditor require discussion and consideration by the OAG before the report is finalised. These interfaces influence where responsibility for key decisions in the planning and performance of the audit ultimately rest.

91. This section begins by briefly outlining:

- the statutory requirements for preparing and auditing local authority accountability documents; each of the Council’s accountability documents (LTCCPs for 2006, 2009; the Long Term Plan for 2012; Annual Reports and Annual Plans for 2003‐2012);

- the basis for appointing the Auditor‐General as the auditor of all public entities, and the expectations for the audit of public entities;

- the role and purpose of an audit;

- the intended scope and objectives of each audit engagement; and

- any other factors directly relevant to understanding the expectations or obligations on the auditor, or on the performance of the audit.

92. I also describe the basis on which Audit New Zealand discharges its obligations as the Council’s auditor and the auditing, assurance and professional standards that the auditor must follow in planning and performing the audit. Collectively, these standards form the essential criteria, or benchmarks, against which I go on to assess Audit New Zealand’s performance in Sections 4.1‐ 4.6.

Statutory requirements for preparing and auditing local authority accountability documents

93. The Local Government Act 2002 (the Act) requires local authorities to prepare and adopt certain key accountability documents, and requires some to be independently audited by the Auditor‐General.

94. Of direct relevance to this review is the requirement for councils to prepare:

- Annual reports – under section 98, a local authority must prepare an annual report in respect of each financial year. The report must contain the information required by Part 3 of Schedule 10 of the Act. Section 99 requires that the annual report also contain the Auditor‐General’s report on certain information, including the local authority’s financial statements for that year.

- Long‐term plans (LTCCPs and LTPs) – under section 93, a local authority must prepare and adopt a long‐term plan that covers at least 10 consecutive financial years and includes the information required by Part 1 of Schedule 10 of the Act. Section 94 requires that the long‐term plan also contain a report from the Auditor‐ General that specifically addresses the matters set out in section 94(1) of the Act.

- Annual plans – under section 95, a local authority must prepare and adopt an annual plan for each financial year and include the information required by Part 2 of Schedule 10 of the Act. There is no requirement that the annual plan be audited.

The role of the Auditor‐General

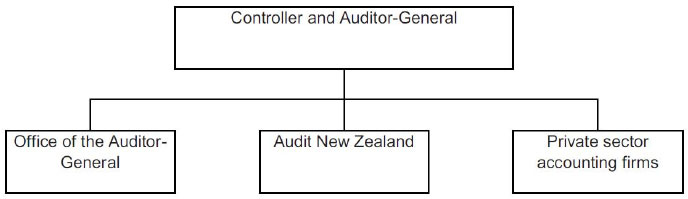

95. In accordance with the Public Audit Act 2001, the Auditor‐General is the auditor of all “public entities”, including local authorities such as the Kaipara District Council. The Auditor‐General appoints Audit New Zealand – a separate business unit accountable to the Auditor‐General – and private sector audit firms to plan, conduct and report on the financial statements of public entities and undertake other auditing functions required by the Public Audit Act. Collectively, Audit New Zealand and the private sector firms who perform audit and assurance engagements on the Auditor General’s behalf are referred to as audit service providers.

96. As the organisational diagram shows, the Office of the Auditor‐General (the OAG) sits alongside Audit New Zealand. Its role is critical to the separation of governance and accountability between the Auditor‐General and the audit service providers. The OAG’s responsibilities include planning the Auditor‐General’s work; setting auditing standards; allocating audits to appointed auditors; overseeing auditors’ performance; carrying out performance audits; undertaking special studies and inquiries; and advising and reporting to Parliament.

97. The OAG directly influences how audit service providers perform audit and assurance services in several ways – by planning the Auditor‐General’s work, by developing and setting auditing standards, and by overseeing auditors’ performance. Thus, the OAG’s discharge of its responsibilities – in so far as they impinge on the audit of local government accountability documents – are directly relevant to my review, even though my terms of reference do not require me to consider the activities and functions of either the OAG or of Audit New Zealand. My decision to do so is based on two reasons:

98. Assessing whether an auditor has adequately planned and performed an audit requires a clear understanding of the professional and ethical standards that have influenced the audit and the auditor’s behaviour. These are set out, in part, in the auditing and assurance standards developed by the OAG.

99. The OAG has been responsible for the methodology and approach used in auditing local authorities’ LTCCPs and LTPs since audits of these planning documents became mandatory. Audit New Zealand is responsible for implementing that methodology, and ensuring its expectations and requirements are met, when it plans and performs any audit engagement. Audit New Zealand must also be aware of any other wider mandated expectations relevant to the Auditor‐General’s role and function.8

100. Therefore, while the terms of reference for this review do not require me to consider the activities and functions of either the OAG or Audit New Zealand, it seems critical to provide a clear picture how both organisations discharged their respective roles and responsibilities in the overall planning and performance of the Council’s audits. It is also essential to see how and where expectations of audit performance were established, and how the reporting of audit results and findings were managed and dealt with.

The purpose of an audit

101. In broad terms, the purpose of an audit is to enhance the degree of confidence intended users can have in considering a matter of accountability (such as, the preparation of a long‐term planning document for consultation, the annual financial statements or the requirement to comply with applicable laws and regulations) that is the responsibility of another party (usually expressed in terms of the responsibilities or obligations of management and/or the governing body of an organisation). The confidence with which intended users regard the auditor’s work and their audit opinion depends on the independence, objectivity and competence of the auditor and their ability to perform a high‐quality audit.

102. Thus, in the context of local authorities, the Local Government Act requires every council to prepare an annual report at the end of each financial year. One of the stated purposes of the annual report is “to promote the local authority’s accountability to the community for the decisions made throughout the year by the local authority”9. The purpose of auditing the annual report is to enhance the degree of confidence that ratepayers (and other intended users) can have in the information prepared and reported by the council. That information may include the results of the council’s operations, its service performance in that financial year, and whether it has complied with the requirements of Schedule 10 of the LGA.

103. In conducting an audit, the auditor’s overall objective is to obtain reasonable assurance that the document (or other matter of accountability) is free from any material misstatement. Where appropriate, the auditor will also seek assurance that the document is presented in a manner consistent with a recognised or prescribed framework for reporting. Such frameworks may cover compliance, preparation, presentation and/or reporting. The auditor achieves these objectives by obtaining sufficient, appropriate audit evidence – all information and explanations that the auditor considers necessary. On the basis of this evidence, the auditor expresses an opinion on the document or other matter of accountability. This is the benchmark that the audit must meet.

104. The concept of reasonable assurance – an important consideration for both the auditor and intended users – must not be misinterpreted. Reasonable assurance is considered to be a high level of assurance. It is reached only when the auditor has obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence to reduce to an acceptably low level any audit risk (that is, the risk that the auditor expresses an inappropriate opinion when the document or other matter of accountability is materially misstated). A material misstatement generally occurs when an annual report omits, or contains differences in, amounts or disclosures, and these differences or omissions would affect the intended users’ overall understanding of the report. Auditors must exercise significant professional judgment to determine whether a material misstatement has been made.

105. Importantly, reasonable assurance does not mean an absolute level of assurance. The auditor does not necessarily examine every transaction or record in order to be ‘reasonably assured’. The auditor does not provide a guarantee of the absolute accuracy of the information set out in the document or other matter of accountability. Nor does an auditor discover or prevent all instances of fraud or non‐compliance with legislative requirements. Finally, an audit is not a guarantee of a council’s future viability.

106. In planning and performing an audit, the auditor understands these inherent limitations. It is recognised that most of the audit evidence from which the auditor draws conclusions and bases their opinion is persuasive rather than conclusive.

107. Consequently, there is an unavoidable risk that some material misstatements or noncompliance may remain undetected when auditing a matter of accountability. Notwithstanding, intended users have the right to expect that the auditor will plan and perform a high‐quality audit to ensure that the overall objectives of the audit are satisfied.

108. When planning and performing audits of a council’s annual report and planning documents, Audit New Zealand prepares and issues an Audit Engagement Letter (AEL) as required by the auditing standards. The AEL is addressed to the mayor as a representative of the council’s governing body. It clearly outlines the purpose or objective of the audit, and states what intended users may expect of the auditor and from the performance of the audit engagement. The AEL also identifies the respective roles and responsibilities of council management and the auditor – both in preparing the annual report or planning document, and performing the audit. The AEL is thus an important means of managing the potential risk of an audit expectation gap.

109. I am satisfied that Audit New Zealand has effectively communicated the audit objectives and responsibilities in every audit engagement. The AEL sufficiently and appropriately addresses those matters required to be covered by the OAG’s auditing standards.

The scope of specific audit engagements

110. As outlined above, Audit New Zealand was appointed by the Auditor‐General to independently audit the Kaipara District Council’s annual report and planning documents. There is no legislative requirement for Audit New Zealand to audit any council’s annual plan and so it was not appointed to do so. However, the auditor generally reviews and considers councils’ annual plans when auditing their annual reports.

111. The scope and objectives of an audit of a council’s annual report differ from those of a planning document. Accordingly, the work that the auditor must perform to obtain a reasonable level of assurance, the opinion the auditor expresses, and the degree to which that opinion can be relied on all differ also. It is important to understand these differences in scope when assessing the sufficiency and appropriateness of the auditor’s work.

Annual reports

112. The audit’s scope includes the council’s financial statements, group of activity statements, and the council’s compliance with the requirements of Schedule 10 of the Act applying to annual reports. The auditor’s report must provide an opinion on whether:

- the council’s financial statements comply with generally accepted accounting practice in New Zealand, and fairly reflect both the council’s financial position at balance date and the financial performance and cash flows for the financial year;

- the council’s group of activity statements comply with generally accepted accounting practice in New Zealand, and fairly reflect the levels of service for the financial year; and

- the council has complied with the requirements of Schedule 10 of the Act that apply to the annual report

Long‐term plans and Long‐term Council Community Plans

113. Unlike an audit of the annual report, the Act specifies the scope of the auditor’s report on the long‐term plan. Section 94(1) requires the auditor to report on:

- the extent to which the council has complied with the requirements of the Act in respect of the long‐term plan; and

- the quality of the information and assumptions underlying the forecast information in the long‐term plan.

114. Importantly, section 94(3) of the Act clarifies that the audit of the long‐term plan must not comment of the merits of the plan’s policy content.

115. These statutory requirements apply to both the preparation and consultation of the initial planning document, and any subsequent amendments of a council’s long‐term plan.

116. Significantly, the above requirements were set out in the 2010 amendment to the Act.10 In the context of this review, they therefore apply only to the audit of the Kaipara District Council’s 2012‐2022 long‐term plan. Earlier audits were subject to the pre‐2010 requirement for the auditor to report on:

- the extent to which a council has complied with the requirements of the Act in respect of the long‐term council community plan;

- the quality of the information and assumptions underlying the forecast information in the long‐term council community plan; and

- the extent to which the forecast information and proposed performance measures in the long‐term council community plan provide an appropriate framework for the meaningful assessment of the actual levels of service provision.

Annual plans

117. As already noted, there is no requirement for Audit New Zealand to audit councils’ annual plans. However, my review considers and assesses whether the auditor has met and satisfied the objectives of the audit, as specified above.

Other factors relevant to audits of council’s annual report and planning documents

118. Other factors which may influence the scope, planning and performance of audits, and expectations of the auditor’s performance, include the following:

Auditing standards

119. Audits of public entities are conducted in accordance with auditing standards that the Auditor‐General issues and publishes (by way of a report to Parliament). These standards are based on those issued by the New Zealand Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (NZAuASB),11 which are in turn based on equivalent international standards. The Auditor‐General adds to, or amends, the NZAuASB’s standards to take account of the particular scope and nature of public entity audits, and may develop separate standards when there is no equivalent NZAuASB standard.

120. Intended audit users can have confidence in the fact that the Auditor‐General’s standards outline appropriate benchmarks and expectations for auditors performing the audit of public entities.

121. This review specifically considers the auditing standards applicable to each audit engagement. Reflecting my terms of reference, I have focused particularly on standards relating to documentation, the consideration of laws and regulations, knowledge of the audit environment, risk assessments and internal control. I have also examined the specific standards dealing with reporting and communication to councils.

Obligation to advise the OAG about problems of performance, waste and probity

122. While performing an audit of a public entity, the auditor is expected to keep in mind the Auditor‐General’s overall role and concerns. These derive from the Public Audit Act 2001 and reflect public and parliamentary expectations of the Auditor‐General as they have emerged over time.

123. In particular, the auditor must be alert to any potential problems with a public entity’s performance, authority, waste and probity. If a significant problem is identified or suspected, the auditor is obliged to consult with, or refer the matter to, the OAG.

124. This expectation sits alongside the auditor’s primary responsibility to plan and perform the audit. While detecting performance, authority, waste and probity issues is not the primary aim of auditing a public entity’s financial statements, they are important considerations the auditor is expected to remain alert to. Standards and guidance are provided in the Auditor‐General’s Auditing Standard 3: The Auditor’s Approach to Issues of Performance, Waste and Probity (AG‐3).

125. In this review, I consider whether the auditor was (or should have been) aware of, matters relating to performance, waste and probity at the Kaipara District Council. I also examine whether those matters were dealt with in accordance with the expectations set out in AG‐3.

Quality control and quality assurance

126. Audits performed by Audit New Zealand must be conducted within an overall quality control framework or system which applies both at an overall firm level (where a private sector audit firm has been appointed to perform an audit) and to each individual audit engagement. The Auditor‐General’s Statement on Quality Control establishes the benchmarks for quality control systems.

127. The terms of reference do not specifically require me to review Audit New Zealand’s overall quality control system. However, I do so because aspects of that system and related policies are directly relevant to the supervision, oversight and peer review of the audits that fall within the scope of my review.

Review methodology

128. The focus of this review is the sufficiency and appropriateness of the work performed by the auditor. The terms of reference do not require me to independently review or audit the Kaipara District Council’s annual report or planning documents. Rather, I base my observations and findings on the documentation and evidence provided in the audit files or other sources (such as the Rates Validation Bill before Parliament).

129. In summary, I have followed the following process in undertaking this review:

Planning the review

- Forming an understanding of the issues associated with the Council and the wastewater project.

- Clarifying the role, purpose and objectives of each audit engagement.

- Determining the audit performance expectations, benchmarks and standards applicable to the planning and performance of the particular audit engagement.

- Considering and assessing the methodology and approach used to plan and perform each audit engagement.

- Identifying key areas of focus – risk assessments, the auditor’s understanding of the entity/management control environment, legislative compliance etc.

Conducting the review

- Reviewing audit files and the documentation and evidence obtained by the auditors.

- Reviewing quality assurance reviews or reports.

- Holding discussions with auditors, relevant OAG staff and Audit New Zealand management.

- Considering and assessing the sufficiency and appropriateness of the audit files, audit evidence and the conclusions reached by the auditor.

- Identifying and confirming key issues and deficiencies.

Preparing the review report

- Drafting findings, conclusions, observations and recommendations.

- Consulting with Audit New Zealand.

Completing the review report

- Finalising and publishing the completed document.

Note on the OAG’s quality assurance review of Audit New Zealand’s work

130. In preparing for this review, I was keen to fully understand the background to the broader OAG inquiry and also the potential implications of reported issues or irregularities relating to the wastewater project. By any measure, the wastewater project was clearly a major Council activity that was likely to significantly impact the annual report, the planning of audits, and the identification of risks. Moreover, the project’s considerable financial implications would have triggered a high level of community interest that the auditor would have been aware of. These factors should have alerted the auditor to their responsibilities under the OAG’s auditing standard that deals specifically with performance, authority, probity and waste. To better appreciate these contextual issues, I consulted several useful information sources including an independent quality assurance review of Audit New Zealand’s audit work on the wastewater project. The review, undertaken by the OAG’s Quality Assurance team, is narrower in scope than my own review: the OAG considered only the 2009 audit of the Council’s LTCCP, and the 2009 and 2010 annual report audits. Notwithstanding these limitations, in the course of my own review I have:

- considered all the analysis, findings and observations contained in the quality assurance review;

- independently confirmed the basis of those findings and observations by referring back to the audit files. I am satisfied that the OAG’s Quality Assurance team reasonably formed its findings on the basis of the documentation and evidence in the audit files, set against the standards expected of the auditor;

- considered Audit New Zealand’s response to the findings of the quality assurance review (which Audit New Zealand largely accepted).

131. I am therefore confident that it is reasonable and appropriate for me to refer to the key observations and conclusions from the OAG’s quality assurance review in making my own independent findings. The OAG review found that the auditor had an inadequate understanding of the wastewater project, and consequently –

- no audit risks associated with the wastewater project were identified;

- the audit files fail to demonstrate that the auditor specifically focused on or tested the implications of the wastewater project;

- no consideration was given by the auditor to the setting of rates required to fund the wastewater project.

132. Audit New Zealand concurred with the overall key findings, conceding that … “the risks associated with the MEWS12 project were not understood and that this impacted the testing and resulting judgements made in the 2009 LTCCP, and 2009 and 2010 annual audits.” However, for completeness, it is noted that Audit New Zealand did not fully agree with all the findings and observations made by the OAG’s quality assurance team. Matters of disagreement were communicated to the OAG’s quality assurance review team. I have reviewed and considered the matters identified in Audit New Zealand’s response as part of my review.

4 Audit New Zealand was appointed to provide audit and assurance services to the Council by the Auditor‐General who, under the Public Audit Act 2001, is auditor for all public entities, including local government.

5 The local Government Act 2002 requires that the Council’s LTCCP and LTP be audited. There is no separate requirement for the Council’s annual plan to be audited and therefore it is not further considered in this report, except to note that there have been no audits performed on Council’s annual plan during the period covered by this review.

6 As at 1 October 2013.

7 All three auditors, appointed by the Auditor‐General to perform the audit of the Council’s annual report and planning document, were employees of Audit New Zealand. Each auditor used the staff and resources of Audit New Zealand (collectively the audit team) to carry out the audit. The audit, and the audit work performed, was subject to Audit New Zealand’s quality control processes and procedures. Overall responsibility for the performance of the audit rests with the appointed auditor.

8 As set out in, or derived from, the Public Audit Act 2001.

9 Section 98 (2) (b) of the Local Government Act 2002.

10 Local Government Act 2002 Amendment Act 2010 (2010 No 124).

11 Prior to 1 July 2011 auditing standards were developed and issued by the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants.

12 Mangawhai EcoCare Wastewater Scheme.