Part 3: The commercial model and public interest

3.1

In this Part, we consider what being part of the public sector means for Boards. We describe three elements of the relationship between the commercial model, the public interest, and the Board's focus on the future. Based on these related perspectives, we observe matters that various people in the Crown-owned company governance system might need to consider further. We focus on the implications for maintaining a future focus, but some of the observations are also applicable to other aspects of governance.

3.2

In summary, there can be tension between the needs of an individual Crown-owned company and the public interest. These tensions include:

- balancing profit-seeking with long-term strategic interest and social responsibility;

- different information requirements than those in the private sector; and

- ensuring that the company's performance is compared to the right benchmarks.

3.3

We also found that being clear about the entity's purpose and how that purpose fits in the wider public sector context helped Boards, monitoring agents, and companies navigate their way through these tensions.

3.4

Creating single-purpose companies with profit-seeking aims and exposure to market forces was intended to make these companies and the public sector as a whole more effective and efficient.

What we heard about the commercial model and its effect on future focus

3.5

Interviewees interpreted how the commercial model's principles should be applied when thinking about the future in two main ways, which reflected different understandings of their purpose and role in the public sector. The two ways of discussing the future were:

- creating value for the Crown-owned company's future (most interviewees had this perspective); and

- creating value for New Zealand's future (a view largely, but not exclusively, held by interviewees at CRIs).

3.6

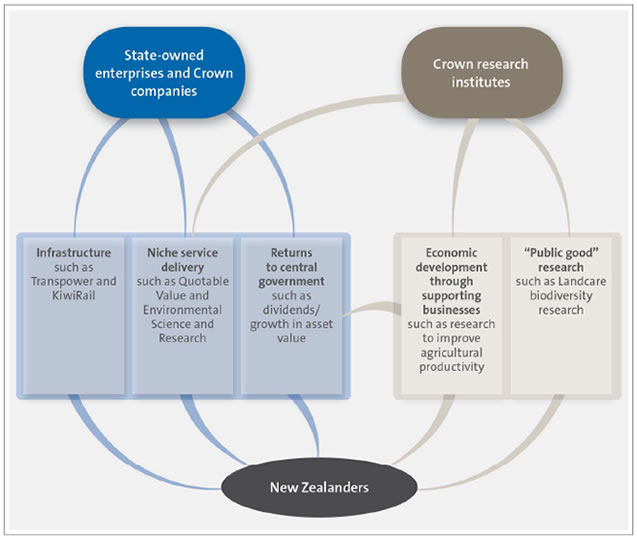

As Figure 3 shows, the SOEs and other Crown companies in this study predominantly described their purposes in terms of infrastructure, niche service delivery, and returns to central government. A very small number of SOEs identified spill-over benefits of their work or capabilities that were available for "whole of government" use. CRIs predominantly identified their purposes in terms of economic development by supporting business and some public good research.

Figure 3

Main purposes of State-owned enterprises, Crown research institutes, and other Crown companies in this study

Managing the Government's long-term investments

What we were heard about balancing short- and long-term interests

3.7

A former Secretary to the Treasury, Graham Scott, has remarked that, in the 1980s, any tensions inherent in the commercial model were deemed inconsequential because commercial models were a "half-way" house to prepare entities for sale to private investors.8 However, by 1997, it had become clear that the benefits of the model, and the strategic significance of some of the assets, meant that Crown-owned companies could be a permanent part of the public sector.

3.8

Today, these tensions are being managed between the individual companies, monitoring agents, and shareholding Ministers. Interviewees described three main ways that these tensions affect them:

- Some chairpersons noted that the model expected companies to be commercially driven. However, mixed objectives, with profit and public interest motivations, had been introduced, sometimes without an appreciation of the effect on dividends and complications in demonstrating the value of this to shareholding Ministers, the public, and other interested parties and in accountability statements.

- The competitive environment sometimes induced Crown-owned companies and other Crown entities or departments to compete. Although the purpose of the model is to expose Crown-owned companies to competition and to ensure that they face the consequences of poor performance or obsolescence, it is also necessary to ensure that the public sector is not wasting resources or unnecessarily duplicating infrastructure or capability. Some interviewees expressed concern that acting in the best interests of the business, as required by relevant legislation, might not be the same as acting in the best interests of the public sector overall.

- Some interviewees asked whether the "one size fits all" approach to Crown-owned companies was appropriate because of differences in their roles, funding models, scale, growth potential, and activities.

Managing assets for public and profit purposes

KiwiRail realised that it had “public good” asset holdings (land under the rail corridor) and assets that could reasonably be expected to make a return on investment. Therefore, KiwiRail separated its public-good assets into a public benefit entity and retained other assets within the parts of the business that could, and should, be operated within the market disciplines of a commercial model.

Sharing expertise

Landcorp identified its practical experience in the farming industry as a strength that the Government used for international meetings and delegation visits to New Zealand. Landcorp was in the process of quantifying that contribution and determining the best way to show the value from these “whole-of-government” contributions.

Our observations on the inherent challenges for governing in the commercial model

3.9

As the owner of these Crown-owned companies on behalf of the public, the Government manages investments for the benefit of all New Zealanders. Along with their commercial incentives, many Crown-owned companies have strategic functions that the public sector and the public rely on.

3.10

There are questions about the extent to which Crown-owned companies should have public sector rights and responsibilities. The tensions include:

- constraints on seeking profit because of social and public responsibilities;

- different information requirements than the private sector; and

- difficulties choosing the right comparator to judge how commercial entities perform.

Comparing performance with similar businesses

What we heard

3.11

Many interviewees noted that Crown-owned companies are often compared to publicly listed companies, for which there is readily available financial information. When monitoring and judging performance, the choice of comparator is crucial in providing useful and relevant feedback for making decisions about the future.

3.12

However, forms of ownership, risk profiles, and shareholder expectations in the private sector are diverse and are not always comparable with Crown-owned companies. For example, SOEs', CRIs', and other Crown companies' different access to capital should affect expectations about their dividends and strategies (see paragraphs 5.19-5.24).

Our observations on understanding and comparing Crown-owned company performance

3.13

A range of comparators, benchmarks, and types of analysis could be useful in understanding how well companies perform and are governed. Although a lot of performance information about large publicly listed companies is readily available, this might not always be the best or only basis for comparison. Boards, monitoring agents, and shareholding Ministers need to be transparent about what they use to compare performance. Transparency is particularly important in showing why and how a comparator is relevant to the company. Transparency will ensure that Parliament, the public, and those involved in the governance of Crown-owned companies can understand descriptions of the companies' performance.

3.14

In paragraphs 2.16-2.27, we set out our previous work reviewing the accountability statements presented to Parliament and entities' reporting against these. The quality and usefulness of information has been a long-standing concern.

3.15

Reinforcing past reporting concerns, we urge members of the Boards of Crown-owned companies and those in monitoring positions to ensure that:

- they fully understand governance and ownership arrangements in the public sector; and

- the information provided through the shareholding Minister to Parliament is a clear account of the company's strategic direction and is supported by relevant performance information that is drawn from the company's current internal management information.

Having a clear purpose

What we heard about purpose and direction

3.16

Most interviewees were clear about the purpose of their Crown-owned company. Further, chairpersons, directors, and chief executives in the same Crown-owned company were consistent about purpose and direction. There was also consistency between the planning horizons9 that interviewees discussed and those recorded in the accountability documents. For example, if interviewees discussed the future mainly in terms of expected events taking place in the next year, then their accountability statements focused mainly on the next year too.

3.17

There was less consistency between the interviewees' comments and the purpose and strategic direction in the accountability statements. Some interviewees stated explicitly that their company's accountability statements did not reflect their own views on the strategic direction of the company.

3.18

Interviewees told us that, at times, the Government's budgeting, planning, and election time frames were shorter than those of their entity – for example, when they were looking to enter new offshore markets. Many interviewees from CRIs remarked that the report of the Crown Research Institute Taskforce (the Taskforce) in February 2010 helped them develop a clearer purpose for their companies within the context of the wider public sector.10 The Taskforce process enabled them to see their strategic contribution in the context of other CRIs, in the context of other government-funded entities, and with the aim of contributing to economic growth.

3.19

By contrast, a portfolio approach was not evident within SOEs, and only infrequent, informal collaboration took place. This was true even when they had shared challenges, such as applying effective governance techniques or managing the public sector aspects of Crown-owned companies.

Our observations about clear purpose

3.20

Crown-owned companies that were clear about how their purpose fits within the wider public sector context appeared to be better positioned to consider New Zealand's future needs. They were more confident that they could contribute to those needs while leading profitable companies. This was particularly observable in CRIs but also in some of the other companies.

3.21

To achieve this confidence, some companies appeared to benefit from considering and being familiar with the context of the Government as a whole, including financial position and risks, when creating and communicating strategy.

3.22

Some interviewees did not appear to have long-term strategies. Although the different purposes and circumstances of Crown-owned companies mean that various planning horizons can be appropriate, we question whether enough attention was always paid to periods beyond immediate projects and challenges.

8: Scott, G. (1997), "Continuity and Change in Public Management: Second Generation Issues in Roles, Responsibilities and Relationships", in Future Issues in Public Management (State Services Commission seminar proceedings) .

9: A planning horizon is the time frame for a plan – for example, one year or 10 years into the future.

10: In October 2009, the Government set up the Crown Research Institute Taskforce to work out how New Zealand could get the greatest benefit from CRIs. Crown Research Institute Taskforce (2010), How to enhance the value of New Zealand's investment in Crown Research Institutes, available at www.msi.govt.nz.

page top